Co-regulating with your little one

Sarah Mundy • 21 June 2020

We're in this together

If I’m being completely honest, I have always struggled to explain what “co-regulation” is. It’s a term banded about frequently, but often without a clear explanation of what it actually means and, most importantly, how we actually do it!

Looking up the definition of co-regulation on Wikipedia (a "continuous unfolding of individual action that is susceptible to being continuously modified by the continuously changing actions of the partner") didn’t clarify things. So, I thought it might be helpful to write a blog about it, with as little psychobabble as possible. I have focused upon what it is, why it’s so important in early childhood. I have also provided some ideas to help parents support their children through co-regulation. Here goes…

What is Emotional Regulation?

Emotional regulation is the ability to respond to an experience without feeling overwhelmed by it (and becoming “dysregulated” – where you lose control of your internal world). It’s about managing our levels of arousal, i.e. how calm or excited we are.

Although no one has it down to a tee (there will always be times that we will struggle to regulate how we are feeling), as we get older we learn to regulate our emotions ourselves. This is known as “self-regulation”. We do this by becoming aware of our feelings, understanding them and learning to express them in a healthy way. We develop a conscious control of our thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

Managing our emotions ourselves requires higher-level thinking. We need to be able to recognise when something triggers us and find a way to bring down our level of arousal before responding. It requires a level of awareness and ability to reflect.

The ability to self-regulate is an important one. The better we are at managing our feelings, the more able we are to manage our behaviours (so important for social relationships). We can focus on what is happening in the moment without becoming overwhelmed, we will feel more balanced emotionally and are less likely to turn to unhealthy coping strategies.

What is Co-Regulation?

“The ability to quickly use the resources of a close other may represent a so-called fast route to emotional regulation” (Sbarra & Hazan, 2008)

As a social species we are pretty much always regulating each other’s emotions and nervous systems, be it our children, partners or colleagues. It’s a natural process. Simply speaking, co-regulation is about how people impact upon each other’s emotional states.

If you have a look at the still face experiment video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=apzXGEbZht0 you will see how a mother’s response to a baby impacts upon them emotionally (warning, even this is only for 2 minutes it is quite distressing to see).

Co-regulation is not a one-way process, but more of an interactive dance in which two people provide moment-to-moment feedback to each other. “Being with” another person can bring our level of arousal down more quickly than trying to manage our feelings ourselves.

This is thought to be because the connection can help calm the lower brain without having to switch on the higher “thinking” part of the brain to find ways to calm.

Why is co-regulation particularly important for children?

When we are very young we rely on others to regulate our feelings - we have limited capacity to cope with them on our own. One of the key tasks of early development is learning to shift from external regulation (relying on others) to internal regulation, i.e. developing the capacity to self-regulate. Little ones need to be taught how to” do this. Not in a sitting down explaining sort of way, but through experiencing others helping them calm - through co-regulation.

When a baby feels an unfamiliar or uncomfortable sensation, they signal to their parent that something is the matter. The parent then steps in to help them regulate how they are feeling – supporting them to calm through non-verbal communication (eye contact, tone of voice, cuddling).

Babies just aren’t born with the ability to self-regulate and it takes some time to learn this skill. Have a think about a perfectly “normal” toddler’s reaction to not getting what they want immediately. It’s hardly a controlled expression of frustration! My three-year old is currently showing me on a daily basis how hard it is to regulate his feelings when you so little. Today he “lost it” when I moved a chair slightly out of place and turned the TV on for him (he needed to do it himself, clearly!).

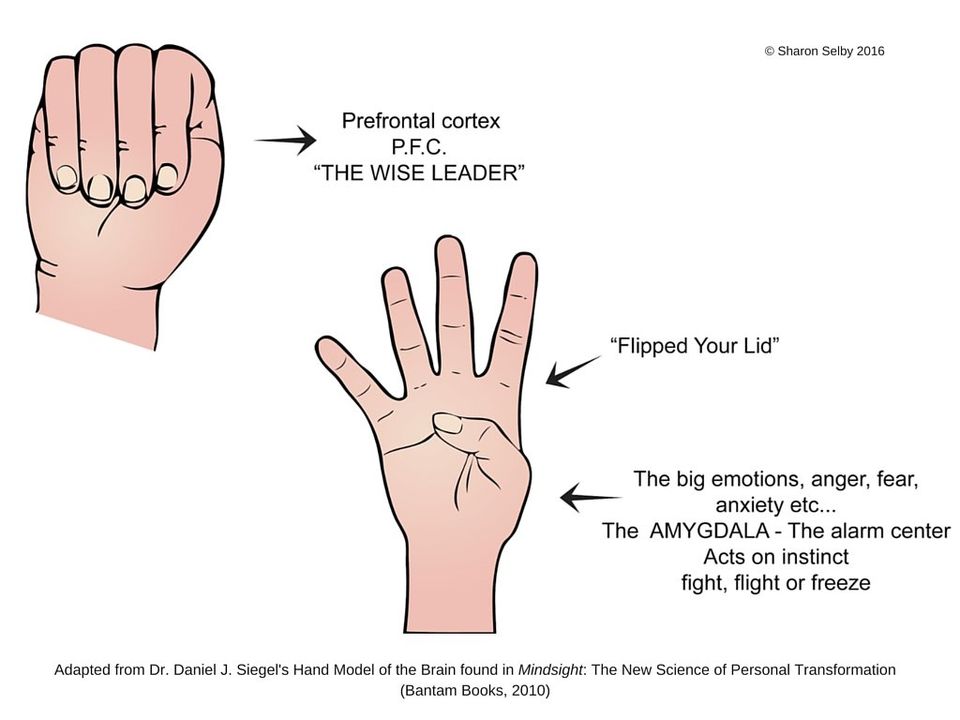

Young children’s brains aren’t developed enough to self-regulate. They need adults to help strengthen those connections between the lower part of the brain (the more reactive survival system) and the higher parts of the brain (the more thinking parts). When children are stressed these two parts of the brain (being simplistic here so excuse me if you are a neurologist!) are less connected with each other, and adults need to help children, through co-regulation, to help develop and strengthen these connections. Siegal and Payne-Bryson talk about “flipping the lid” in the Whole Brain Child. Co-regulating helps put the lid back on!

The more we are able to co-regulate a child’s feelings, the quicker they will learn to self-regulate. I think, historically, we have often assumed that children have more control over their feelings (and resulting behaviours) than they actually do and have expected them to learn to manage their emotions earlier than they can.

When children are struggling we need to be with them, help them calm and help them learn to understand what they are feeling. Only then will they be able to learn to do this themselves in the future.

How do we do it?

It can be helpful to stop and think how we, as parents, are co-regulating our children’s feelings when they are overwhelmed (“dysregulated”) and unable to manage on their own.

If you have read my previous blogs, you will know that I love the PACE model. Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy are all qualities which help us co-regulate our children’s feelings. Approaching your children with this attitude will help you (and them) no end.

We co-regulate by offering a warm, calm response. When children feel overwhelmed your approach helps them learn to understand and express their feelings in a positive way. Try to do the following:

- Notice and label what they are feeling (tune into the emotions driving their behaviours). Siegal and Payne-Bryson talk about naming the feelings to tame them. When they know what they are feeling they will find it easier to understand and manage them.

- Mirror what they are feeling. People often suggest you support a child through a gentle and quiet voice, but I would always try to meet them where they are emotionally. Try to match their mood non-verbally – not through getting angry when they are but by increasing your rate of speech. By meeting them at their level you can bring the emotional temperature down. Just think how annoying it is when someone tells you to “calm down” in a slow and quiet voice when you are stressed!

- Show them you can cope with it – remain in control of your own feelings, help them feel contained.

- Find ways to help them feel soothed through non-verbal communication. Big feelings respond much better to non-verbal than verbal communication. This might include physical touch, eye-contact and a sing-song tone of voice.

- Let them know that you understand what they are feeling and that it is OK and that you are helping them find other ways, more helpful ways, to show this.

- You can reflect with them later what their body felt like when they were out of control to help them notice their own feelings.

- Give the message “we’re in this together” and that you are available to help them when they are struggling.

What about us?

The more able we are to regulate our own feelings and connect with our children’s, the better we can help them understand and manage how they are feeling and the calmer we will both be

(sometimes easier said than done in the midst of a meltdown!). How able we are to co-regulate depends on our own emotional state, and how regulated we are. This can affect how we read a child’s need for help, how we make sense of it, and what we do. We don’t always get it right and that’s OK!

I’m always going on about self-care and how, as parents, if we don’t actively focus on this we are not only modelling to our children that we don’t need to look after ourselves but also running on empty. It’s so much harder to help children when we are in a dysregulated state ourselves. Even though adults are much more able to regulate their own feelings, we mustn’t forget that having others around to help us can bring help us no end – co-regulation is relevant across the life span.

I remembered this recently when, having been with just my children and partner for months, without seeing friends, siblings or parents, I was losing my way. I was getting irritated easily, finding the children pushing my buttons all too often, becoming fed up and feeling unappreciated. They obviously picked up on this (I’m not very good a hiding my mood) and an unhealthy cycle of negative emotions started – not surprising as emotions are contagious.

It got to the point that my middle son asked if he could have more “daddy days” as “mummy days” weren’t fun (because I was being so grumpy: unfortunately he was spot on). This made me realise that I really was struggling to manage my emotional world on my own, that my children and partner were inadvertently feeding into this and I needed to seek help elsewhere.

I called my mum who came around as soon as she could. Whilst she couldn’t give me a hug, and looked a bit weird in a mask, her support, empathy and acceptance, verbal and non-verbal was just what I needed. I might be in my forties, but sometimes I still need my own mum to help me regulate my feelings (thanks mum!).

If you have any questions about Parenting Through Stories and our approach to supporting parents and children, then please don't hesitate to get in touch.

Take care of yourselves and each other,

Sarah

Our Parenting Handbook is full of practical tips and insights into a child's development which can help navigating parenting that little bit easier. Our lift-the-flap children's book, Please Stay Here - I Want You Near, supports little ones through separation anxiety - a very common challenge, especially at the moment. Both are available to buy here https://bit.ly/314RpU6

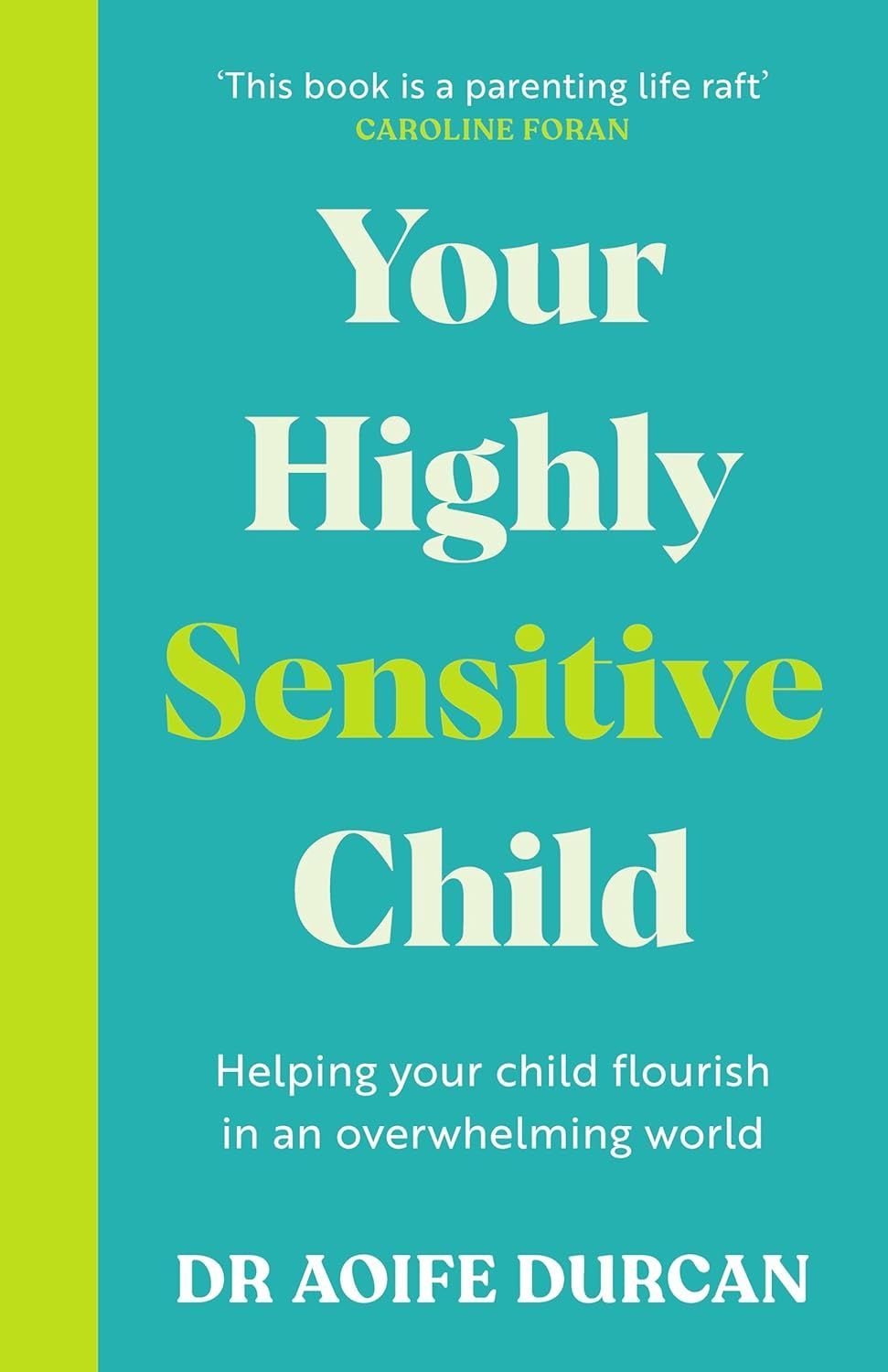

“My biggest piece of parenting advice is to try your best to let your child feel really seen by you. Even when their behaviour is confusing and you don’t understand, let them know you are trying to and that they mean the world to you” The goal of the book is to help parents understand their highly sensitive child as well as provide us with some tools to help them flourish. She talks about wanting children to “feel understood, validated and loved for who they are deep down…and empowered in whatever way their wonderful selves are wired”. This fits so beautifully with my main approach in therapy but oh so relevant to parenting and relationships in general – the PACE model (Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy). A clear and compassionate read “It is perfectly normal for some children to seek more connection and soothing. They may want more hugs, more closeness and more holding, and that is not something we need to fear or pathologise”. I could tell straight away what a good clinician Aoife must be from the way she writes – with such connection, empathy and understanding of both parents and children’s experiences. As a parent who has (what I’d now call a highly sensitive child) it really connected with me on a personal level. Her explanation of psychological theories is amazingly clear – something which is sometimes lacking in books written by professionals. This is particularly impressive as she beautifully validates emotive topics (such as sleep and our own history). Summary This book so beautifully focuses on children and adults and, I suspect, many of us with highly sensitive children would fit the profile ourselves. It will be a great help to many – providing ways to support both our children but to help us flourish as well. I knew a lot of the theory and ideas in the book (as a psychologist of 20 years I was relieved about that!) but for parents there is a wealth of new knowledge and for me it was a useful reminder. Here is a breakdown chapter by chapter: Chapter 1: Understanding your sensitive child Aoife talks about what sensitive means (something I would love to explore further with her in terms of temperament, neurodivergence and early experiences – all of which she describes but something I want to know more about). Aoife describes “the difference between high sensitivity and these other forms of neurodivergence is that they encompass features of a distinct brain style beyond sensitivity alone”, acknowledging that there can be concern that identifying a trait of high sensitivity may lead to a missed diagnosis of other forms of neurodivergence and that it has been somewhat controversial a term in the neurodivergent community. She talks about the importance of co-regulation (something I bang on about a lot!) and describes goodness of fit (how well our child’s environment fits their unique needs) which was a good reminder to me that my children need different things to thrive. Throughout the book Aoife weaves in case studies, and I love the way she shares a deep understanding with other parents who have often experienced “huge amounts of self-blame and shame” when looking after their highly sensitive child. I love her deeper dive into sensitivity, where she outlines Dr Elaine Aron’s main characteristics of sensitivity with the acronym DOES (depth of processing, overstimulation, emotional reactivity and sensing the subtleties). Sometimes I thought I was reading specifically about my son (and sometimes myself!). Chapter 2: Your child’s window of tolerance “If we keep coming back to the premise that our children are acting mainly from their emotional brain and an underdeveloped ability for impulse control, it helps us understand a little more. The more we pause ourselves and imagine how it feels to be in their shoes, their behaviour often makes sense”. She describes highly sensitive children as orchids, with very big hearts and highlights that there is an increased activation in areas of the brain which are associated with awareness, integration of sensory information, empathy and action planning (I’m going to ask more about this research when we have our live). It made so much sense that children with more finely tuned nervous systems, who detect danger more easily than others are more likely to be on edge. A much better way of understanding children who are struggling than thinking their behaviour is bad – they are just responding to what signals their body is sending to them. After helping us understand what may be going on for highly sensitive children, Aoife talks about the window of tolerance, sleep, transitions and the three R’s (regulate, relate and reason). I scribbled a lot on this chapter as it resonated so much with me and served some lovely reminders to me as a parent and psychologist, particularly when Aoife highlighted how children can become ashamed of their actions (that they have little control of) and how anger can turn to tears when we respond with empathy and kindness. Chapter 3: Our own life history I love this chapter! Many parenting books forget that we are key to our child’s emotional wellbeing and leave us out! Aoife talks about our own critical voice, comparing ourselves with others, vulnerability and our emotional and physical health. She outlined the RAIN of self-compassion model (Recognise, Allow, Investigate and Nurture) which was new (and helpful) to me and, I suspect, draws on her experience of working with adults I suspect). It is written warmly and compassionately and is much more comprehensive than you normally see. There was not one inch of parent shaming which can sometimes slip into books (inadvertently). Chapter 4: How we learn to protect ourselves We often focus on what we as adults are getting wrong but Aoife clearly outlines how we as well as our children learn to cope to protect ourselves (which fits really nicely with attachment theory which I draw on heavily in my work). She describes “protectors” such as perfectionism, people-pleasing, self-soothing (I’d always thought of this as a good thing) and control. Helpfully, this chapter includes practical grounding and soothing techniques. Chapter 5: Temperament, being ‘shy’ and understanding anxiety “ separating from \us will often cause our more sensitive souls stress. The stress makes so much sense (we are their safe place)l…In an ideal world, we really want the childcare setting to be another nurturing, warm and attuned relationship our child has in their life” Aoife focuses on some of the things that highly sensitive children may find harder in this chapter – whilst often reframing them with a positive spin e.g. the ‘pause to check’ system). She talks about separation anxiety, temperament, childcare, big emotions after school and helping children move into their “optimal zone of tolerance” to help them learn new skills without feeling overwhelmed. I like the way worries are framed as a powerful coping protector that manifests when we feel scared, sad or like we are not good enough…it helps to go straight to the underlying need our child may be communicating rather than get caught up in the cognitive content of the worries – to feel safe, loved, validated, understood and accepted, True confidence comes from knowing deep down at your core that \you are a worthy person, and you are lovable as you are. We can be confident and quiet, and being ‘shy’ is not a negative thing According to Aoife, 70% of \highly sensitive people identify with the trait of introversion (not mine). I love the term “introverted extravert” (a new one to me) whereby the extrovert in someone gets a lot from the external world but their nervous system is easily overstimulated (remember DOES from chapter 1?). there are some \helpful tips on supporting children who are described as “shy” – both for them and for others trying to get them out of their shell (more about the others’ needs than the child’s?) Certainly something I've been guilty of). Chapter 6: The empath “Learning to be with painful feelings, without trying to fix them, is so connecting for our relationships -especially for empaths. We need to understand that we can't talk them out of their feelings. The only way their emotions move is by giving them the space to be felt. It is only then we can begin thinking of ideas that may help ” This chapter helps (worn out) parents understand their child's big feelings. Aoife talks about anger, getting suck in emotions and how important it is not to dismiss them, which can lead to a deep sense of confusion. She describes how her own deep-feeling nervous system has experienced an emotion so strongly that it takes time to lift and, when it hasn’t been seen and understood, it takes longer to process. This was so helpful for understanding my son, who picks up on emotions so easily (he even knows when I'm getting my period before I do!). Chapter 7: Criticism and being ‘good’ Criticism can feel so painful for highly sensitive children – even when it's meant as constructive feedback. Aoife talks about how important it is to validate their experiences, even if their reaction seems a bit extreme to us! She describes ways to help them find their voice and move forward when feeling criticised. This chapter also talks about how highly sensitive children can get really upset about doing the right thing or feeling like they have disappointed you. I love her point that we may expect more from them as they are so emotionally in tune and articulate – but this can miss the point that they are driven mainly from their emotional brain with limited impulse control. She talks about boundaries and children who apologise too much (or too little!) as well as how to support them when they feel misunderstood. Chapter 8: Navigating painful emotions “Sadness can be a familiar emotion for a sensitive soul. Feeling the world deeply and noticing how painful life can be sometimes, and experiencing grief, loss, feeling excluded, rejection and being misunderstood can evoke feelings of sadness and loneliness.” Its so hard when our children are experiencing deeply painful emotions and we feel a bit stuck as to what to do., this chapter talks about trust, grief, sibling relationships and feeling different, outlining ways you can support your child to make sense of their experiences and emotions – through their connected relationship with you. Chapter 9: Understanding our strong-willed children Aoife goes back to basics in this chapter, delightfully explaining why some of the traditional behavioural methods of parenting are a particularly bad fit with our more strong-willed children (as I have learnt through experience over the years!). she talks about the need to give children a sense of agency, control and flexibility and provides a lovely reactivity guide (screening list) to help us understand what our children may be communicating with us. Again, Aoife highlights the importance of co-regulation as well as understanding and managing our response. She also describes how repair is key – something I talk about a lot. Time in is outlined (as an alternative to time out…something that I’ve talked about before in previous posts). Chapter 10: Sensory sensitivities As psychologists (particularly those of us that trained 20 years ago!) we weren’t well versed in the importance of sensory profiles – but it is now so clear that our mind and body work together and that we need to be aware of both if we are going to support children’s emotional and behavioural development. This chapter outlines the different senses and how our bodies read our environment, which is hugely different for each and every one of us. She talks about both parents' and children’s sensory needs and how we can empower sensory-sensitive children. Chapter 11: My wish for every parent The last chapter of Aoife’s book is beautifully written, outlining what she wishes for parents. She talks about comparison traps, trusting yourself, asking for help, avoiding self-blame and bringing more fun and play into your (and your children’s) lives. I am always a bit biased to chapters about parents as we are so important if we are going to be the best parents we can be…and Aoife highlights this wonderfully here.

“Playing with our kids and really getting to know them is a little like scuba diving. From above the surface of the water, it’s hard to know what’s really happening down there under the waves. But when you take the plunge, you discover this whole other world: dynamic, real, fascinating, beautiful and full of life” (page 5) Why is play important? · Play is in children’s nature – it’s their first language and helps them learn with creativity, joy and connection · It builds crucial skills and reduces unwanted behaviours. Children build confidence, resilience and self-understanding through play. And with this comes a reduction in fighting, rudeness and tantrums (a reduction not an extinction – these are all part and parcel of childhood!) · It gives children appropriate ways to express and process their emotions and can be a powerful way to process what has happened and heal after difficult experiences. · It can help us connect with our children and enjoy being with them. It helps us understand their inner world and delight in them, building their self-esteem What if we don’t know how to play? (something I hear from lots of parents) · If we struggle to play it’s not our fault – our brains grow and change since we were children. · We have to relearn what it means to think and play like a child · For those of us who haven’t had playful parents when we were growing up it may be harder – but it’s never too late to learn What are the strategies that the authors talk about? This is a very brief summary – it’s well worth reading the book for a full exploration with lovely illustrations, example and science behind the strategies. · Think Out Loud o Why? This helps children understand their thoughts, feelings, wishes, intentions and desires more. When we do this it helps them learn that others can understand them and help them understand themselves. We help children to pay attention to what is happening inside themselves so they can develop positive, conscious, international responses rather than the default reaction with no awareness! o How? We do this by observing and narrating what we see in our children’s play, commenting on mental and emotional stages. We do this by observing and attuning, coming up with a hypothesis, saying it out loud (don’t worry if your guess is wrong – your child normally lets you know!) · Make Yourself a Mirror o Why: help children understand their emotional life and enhance their connection with and empathy for others. o How do we help children exercise the empathy muscle? (love this term!). Observe and attune into what your child is feeling with your body, face and voice, activate your child’s mirror system and remember empathy is mainly conveyed non-verbally (as well as verbally) · Bring Emotions to Life o Why: help children recognise, manage and express feelings. o How: observe and attune (as you may have noticed, we always start with this!) watching for emotional cues, act out your part adding emotions to your character (if your child invites you into their play) – alternatively, touch on emotions as the narrator of their play. · Dial Intensity Up or Down (this feels more about general parenting that play) o Why: this helps children regulate their emotions and actions when they are struggling and helps them learn that someone will be there for the when out of control. o How: Observe and attune – looking out for your child becoming dysregulated. Chase the why (I love this phrase) – see if you can work out what their dysregulation may be about? Look beyond the behaviour (if you want to learn more about this read Mona Delahooke’s work – it’s brilliant!). Dial the intensity up (through cooling things off ) or down (through starting low and going slow) Regulate and repair o Scaffold and Stretch: Why? Help children learn resilience in the face of difficult situations and show them others can show up when things get hard. How? This is about helping your child face something difficult in a low stakes way – through play. Firstly, observe and attune – to see if they may benefit from some support. Then offer scaffolding and stretching – it’s getting the balance right between not taking over when there’s a little struggle (my tendency!) and not letting them struggle so much they get stressed and don’t learn… Narrate to Integrate · Why? using stories (obviously my favourite thing!) to help children understand and deal with difficult situations. · How? Observe and attune (did you guess that?!), oscillate (between different halves of the brain – use logic and emotions), integrate and elevate. Set Playtime Parameters Why: boundaries teach children how to make positive decisions and help them feel safer. Children need limits, connection, structure and nurture How? Set some rules for play by taking care of yourself and of the space (try not to make it too chaotic!). Remember you are the pit crew not the race engineer (!). If you’ve had to set a limit then acknowledge the desire but keep the limit and offer alternatives. The authors set some good ideas for transition tips (as transition out of play can be HARD!). Finally, Tina and Georgie end with the importance of being playful outside of the playroom. For those of you that have read my parenting handbook and know about my love about the PACE model you’ll have guessed that I was pleased to see this in! Overall, a great read…well worth a delve

Little children can be so confusing (and confused!). Sometimes it’s hard to know what they need from you - a three-year-old demands that she wants her cheese in a big piece one day and then cries because it’s not cut up the next. She wants you to hold her hand to go to the toilet in the morning, but later gets cross when you try to do the same. We’ve all been there, faced with the - sometimes baffling - behaviours of the small humans that surround us, wondering how to respond to their inconsistent requests. Perhaps it’s reassuring to realise that these seemingly random behaviours are actually quite natural - stages through which each child progresses. In a bid to help you support your growing pre-schoolers more effectively, this blog talks about some of the things (there are many!) happening inside their heads and how you can support them with what’s going on. What’s Happening Inside a Three-Year-Old’s Brain?

What was your favourite story when you were growing up? Was it a traditional fairy tale like Cinderella? Was it a popular picture book like The Very Hungry Caterpillar or The Gruffalo? Or was it a great adventure story like CS Lewis’ Narnia series or JK Rowling’s Harry Potter? Mine was Dogger by Shirley Hughes. Funny that the first book I wrote was about separation anxiety! For many of us, sharing and reading books was an important part of childhood, even more so before the advent of distracting screens and 24/7 streaming. I have fond memories of curling up in bed, half asleep, as my mum or dad read to me complete with silly voices and giggles aplenty. It's not just books though - you can make your own stories up too. I tell my little one a story about “Grizzly Bear with the Curly Hair” every night. It’s evolved to be a lovely family tradition, with my older children sometimes coming to join in. This is a wonderful way to stimulate both mine and my children’s imagination and what I most love about it is how the narrative is co-constructed – I am no longer allowed to be the sole story-teller, my son has to be part of it too! A 2018 research study found that nowadays only 30% of parents read to their children daily and I can’t help feeling that’s a bit sad. Especially given the many benefits of sharing story time go far beyond pure entertainment.

I thought I’d do a post on guilt and shame, feelings which are often used interchangeably but, from my understanding are pretty different. A quick whizz through some child development When we are little, particularly when we start testing the boundaries during toddlerhood, parents need to intervene to keep children safe. For those of you with little ones the word “NO” probably comes out more than you would like it to! This is a normal part of development – children exploring without an understanding of risks, and needing adult involvement to know when to stop. When a child is asked to stop doing something, which was most probably led by curiosity (can I touch that hot thing in the fire place?!), they are likely to experience shame. It’s not a nice feeling but is quickly regulated when a parent explains their motive and repairs the rupture in the relationship. “I’m sorry that I raised my voice, I know you were just exploring but it’s dangerous to touch fires” and so on. This gives the message that the parent is still there for the child and that they are accepted for who they are. The parent is showing them that their behaviour not OK, but that they are. This sort of parenting, when reasonably consistent, leads to a child feeling guilt rather than shame. “Oops, I shouldn’t have done that, how can I make amends?” (obviously not so clearly thought out for little ones but you get the gist). .

As a newborn, we look to our parents for everything. To feed us, to comfort us and to protect us. If they give us this safety and security, a healthy emotional bond develops. Research shows that this attachment relationship is a crucial building block of a child’s development, helping them to grow socially, emotionally, behaviourally and intellectually. But what happens when children begin to spend time with other caregivers, outside of the home and away from their parents? Do they develop similar relationships with the nursery staff, childminders or pre-school teachers that look after them? And what does this mean for you if you’re working in Early Years?

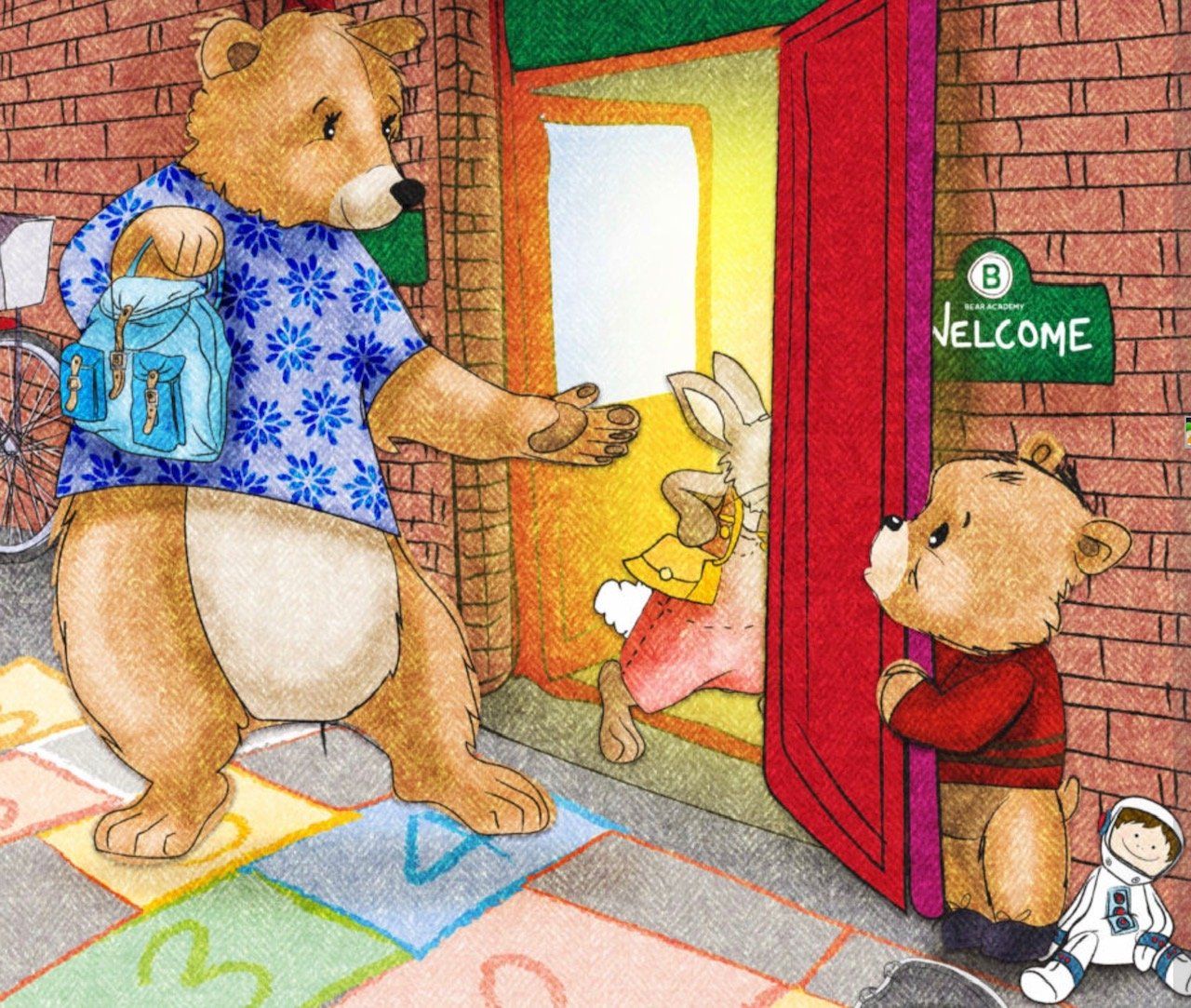

If you work in an early years setting, you’ll be quite familiar with the scene. You’re welcoming the children and getting them settled at the start of the day, checking in with them and showing them what activities you have planned. Suddenly, you hear shouting and crying as a stressed-looking mum tries to detach her small child from her leg. You feel for her, you really do; this child regularly clings to her on arrival - the anxiety is palpable. It’s distressing for everyone involved. For Mum, for the child, for the other children who are already in the room, and not least for you. You know from experience that they will settle down and be OK, but that doesn’t make it any easier in the moment. And you know, too, that poor Mum has headed off to work feeling guilty and upset, so it’s unsurprising when she phones 15 minutes later seeking reassurance from you. These experience are likely to be more pronounced at the moment, with children having fewer, if any, opportunities to practice separating from their parents, with collective anxiety at a huge level and with normal settling in sessions, with parents in the room, being unavailable. What is separation anxiety?

Where do I start? Attachment is a HUGE topic, with decades of research highlighting how important it is to a child’s development. But do you know what an attachment relationship actually is? And why it’s so important? Do you know what helps children develop more secure attachment relationships? With different approaches and a number of terms banded around it can feel so confusing. This blog addresses these questions and focuses upon ways that parents and educational settings can put attachment theory into practice. It is based upon my experience as a Clinical Psychologist. For over 15 years I have been drawing upon attachment theory to inform my work with parents and children. I’ve tried to ensure that my suggestions are user-friendly. As a mum of three I have learnt that theory does not always feel that easy to translate into practice. We can feel pressured to get it right all of the time (apologies to the clients I worked with before having my own children!). The beauty of attachment theory is that we don’t have to be perfect. Just good enough. As with anything scientific there can be a lot of jargon – I have put the key words in italics and tried to write with minimal psychobabble. I do hope you enjoy it! What is attachment (in a nutshell)?

In case you hadn’t noticed, Christmas is coming, and fast! It’s different this year, without nativity plays, big get togethers and light turn-ons. But it’s still happening, as both we, and our children well know! My three-year-old is already telling me that it is “Christmas tomorrow” on a daily basis (to be fair he also thinks it’s still Halloween so he’s not particularly accurate in his understanding of seasonal activities!). He is, however, starting to get excited. He’s remembering the elves escapades from last year, asking when they are coming back (I still haven’t found them in my cluttered house!). Why I added the nightly task of creating funny Elf scenes throughout December to the already huge list of Christmas jobs is beyond me, but at least he likes it! I was also quite proud of last year’s zip wire adventure.

I know the gold standard for writing blogs is to deliver them on a fortnightly basis. I’ve been a bit remiss as this is my first one in months! What a better topic to start with then than why it is OK not to get things right all the time. Perfection is unobtainable, but it does seem to be something that we are pushed to do. The number of posts out there on mum guilt is astonishing. Over the last year we have been expected to juggle life in a way that does not seem possible. Many of us have been coping with (or trying to) being teachers, parents and professionals, three full time jobs all at the same time! This has left me wondering whether it’s actually possible to do anything well enough! And then along comes Christmas (gulp!). I’m hoping that reading this will leave you feeling happier with how you are doing as a parent, that you will realise that buying into the pressure to get it “right” is not helpful, and that you will learn that the attachment research highlights how we don’t need to be perfect to raise happy and healthy children. Children don’t need us all of the time. They need is a parent who knows they are good enough for them, accepts their foibles, makes and owns mistakes, and can manage their own emotional world. Forget Perfection - Strive for Good Enough Parents can feel a great deal of guilt around their work/life balance. Guilt can actually be a helpful emotion, allowing you to reflect on what is, and isn’t working. However, when you have little control over the things you want to change, it can feel overwhelming. The first thing you need to remember is that you are doing your best, and that is good enough. Interestingly, an article in the Economist reported that we spend twice as much time with our children as parents did 50 years ago (The Economist, November 27th 2017), suggesting that we are already much more active in our parenting than we used to be. “Good enough” is key to parenting. Research into attachment, which is important to children’s development, highlights how we should strive to be good enough, not perfect. A recent study on infant attachment found that parents need to be “in tune” with their babies about 50% of the time in order to develop secure attachment relationships (Woodhouse et al., 2019). So, if you’re getting it right about half the time, you’re onto something! Quality of Time is Far More Important than Quantity