Are Early Years staff attachment figures for preschool children?

Attachment is recognised as extremely important within parenting literature. It’s well known that from around 6 months, babies tend to show a preference for their primary caregiver. If that parent is predictable, nurturing and responds sensitively to their child’s needs, a secure bond will develop helping them to feel loved and cared for and giving them a positive message about themselves and future relationships. See our previous blog to read more about attachment.

There’s a growing understanding about the importance of a secure attachment and the impact its absence can have on the life chances of a child. Indeed, evidence shows that children and young people who have had insecure attachments are more likely to struggle in terms of their social, emotional and behavioural development.

Toddlers and pre-schoolers learn to navigate the world through exploration and curiosity. In order to feel secure enough to do this, however, they need to feel they have a safe base to return to, a reliable caregiver who will reassure them that everything is OK. When enjoying new experiences and discovering new places a little one will often return again and again to this ‘safe haven’ to recharge between adventures.

This animation, the Circle of Security, perfectly explains this innate need, showing how children need us to allow them the space to explore with our support, knowing that when they come back to us we will welcome them and help them to manage their thoughts and feelings with kindness and empathy.

Relationships with others are also positively influenced by a secure attachment. Little ones who feel secure in their attachment will expect other relationships to also be enjoyable and reciprocal. This is because they form an "internal working model" based upon their experiences with their caregivers, which acts as a template to predict how they see themselves, others and the world around them.

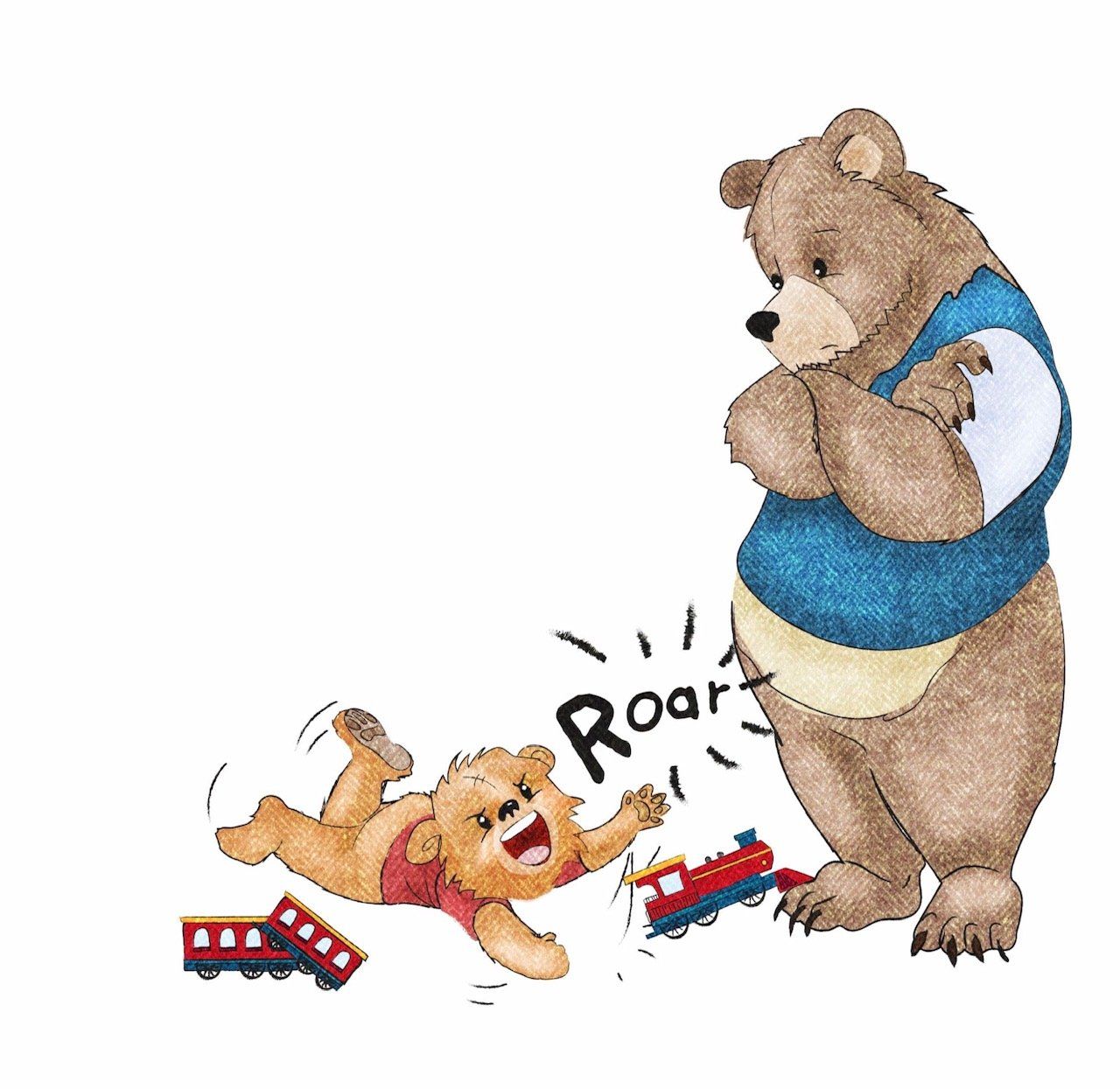

Secure attachment relationships have been shown to literally shape the way the brain develops, helping children cope with feelings, relate to others and learn how to self-regulate their emotions. Without responsive parenting throughout the early years, children can get stuck with difficult feelings, not knowing how to manage them and leading to poorer social and emotional outcomes in later life.

We are currently seeing a huge movement to support vulnerable children, or those whose attachment needs remain unmet, in schools around the UK. Recognising the importance of this, Academics at Bath Spa University have set up a wonderful Attachment Awareness and Emotion Coaching project working to promote well-being and positive learning outcomes for school-aged children who are struggling.

As Early Years professionals we do have the opportunity to help. As very young children enter the childcare setting, EY teachers naturally earn the position of ‘substitute parent’ when little ones find themselves away from their primary caregiver for the first time. And very often we will begin to form an attachment with those in our care, making us an extremely important influence in their early lives. Something that should be treated as both an honour and a huge responsibility.

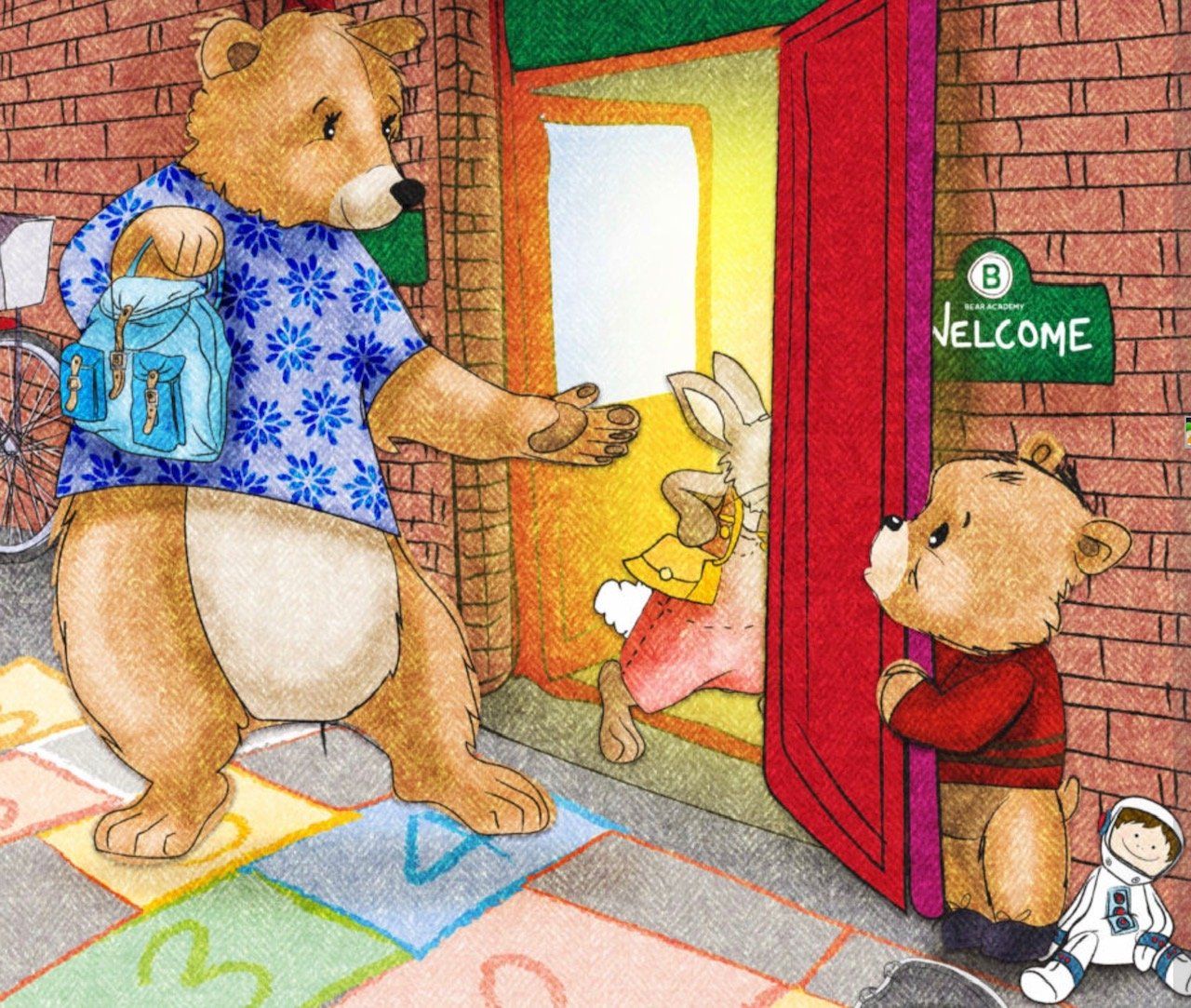

I was thrilled the other day when my son went to pre-school, somewhere he generally feels safe at but which has wobbled him recently due to changes (new staff and new teachers). He left my side when I said goodbye and went straight to his key-worker, checking out the new member of staff whilst using his key worker as his safety net (he wouldn’t let her go and she was tuned in to his needs and let him stay close). I left knowing that he was in safe hands and able to use her as a secure base. This wasn’t only good for his emotional wellbeing but mine too!

Guidelines in the EYFS have changed the phrase ‘key worker’ to ‘key person’ in order to focus on the nature of the relationship between carer and child. But fostering an attachment relationship in an EY setting, naturally requires an intimate relationship with someone else’s little one. This can feel complicated and difficult to some. But should it?

In fact, research suggests there are benefits to forming a close bond with adults other than parents. It’s been found that children seem to do best when they have at least three adults who consistently demonstrate that they love and care about them. It’s been theorised that spending close one-on-one time with a variety of caregivers can help little ones practise reading facial expressions and begin to make sense of the differences between people.

It’s been proven that the loving relationships that under-threes have with their carers are the key predictor of social emotional development as well as physical health. But brain development happens around the clock, not only when children are with their parents. It’s vital they experience these secure, protective relationships at all times. And perhaps, arguably the most important time to focus on forming a strong relationship with a child is when you have a concern that attachment isn’t happening properly at home.

But there are challenges too to achieving attachment with all children in a nursery setting. All sorts of complex emotions come into play when we think of our child becoming attached to a non-parental caregiver, one who is not such a long-term fixture in their life. What will happen when the EY teacher moves on to a different job, or takes time off? Will the child struggle to adjust and will other carers be left to deal with the consequences? How can this be managed when the ratio of staff to children is high? And what if parents are not comfortable with their children forming a close bond with another adult?

These are all questions to ask yourself and colleagues, perhaps with the knowledge that children experiencing you as a secure base can only be a good thing and that, if you do leave that you make sure there is another containing and supportive adult by their side. They will internalise their experiences with you and you will build their template of relationships as being safe and supportive.

It’s vital that children get the right quality of relationship to nurture them and allow them to grow and thrive. When they’re not at home with their parents, or if they’re not getting what they need from that home environment, then a pseudo-parent in the form of an EY teacher or caregiver should be able to go some way to providing that vital developmental required. No, it won’t solve the difficulties in their attachment relationship at home, and many of the dynamics may be played out in the early years setting. But, it will provide them with another model of templates to learn from.

Those first 5 years of a child’s live have been found to be so important that it’s crucial we, as caregivers, do everything in our power to get this right. Not acting as a surrogate parent, but rather building a professional relationship that complements the parent-child relationship and upholds the rights of the child as the central point of reference.

If you’re working in early years, there are plenty of ways you can use your role to support the children in your care to develop secure attachment. I list a few below:

· When trying to develop a secure bond with a young child, I often suggest the PACE model (see previous blog about PACE) as an approach. Ensuring playfulness, acceptance, curiosity and empathy in all your interactions can help the child feel understood and more connected to you.

· If you feel things aren’t right in terms of attachment at home don’t be afraid to explore this with a parent or carer. You are also there to support them, and many times they will be grateful for advice from someone who knows their child well. You could suggest resources such as my Parenting Handbook to help explain the concept of attachment and offer tips and advice to improve parenting skills at home. But don’t forget, if you have significant concerns you need to report them using the latest safeguarding protocols.

It’s also helpful to remember that, when a little one associates you with safety that they may be a bit wobbled when you are not there (yes, you need a break too!). Although we advocate a key person it can also useful for each child to get used to being looked after by more than one carer. If you know you have a close bond with a particular child and you won’t be in the next time they are there, prepare them by explaining to them that you will be away but you’ll see them the next time and they will be safe and looked after by someone else. You may even wish to notify the parent so they can help prepare the child for their arrival during the next session.

If you want to go the extra mile (in my experience this is what EY professionals do on a daily basis!) you can also let children know you are holding them in mind if they aren’t at pre-school. For example, if they can’t come in because they’re unwell or needing to isolate, why not send a video or a picture to let them know you are thinking about them and looking forward to seeing them again. My son’s preschool has already prepared activities for me to do with him this afternoon, celebrating his father’s cultural identity. This thoughtfulness not only strengthens the positive connection between home and school but shows my son that his teachers are interested in him as a person. It also means I don’t have to prepare anything for my mummy afternoon. Win win!

We cannot ignore the crucial role that consistent, loving care plays in brain development of a preschool aged child. We must focus on supporting children's relational needs in early years settings, as well as encouraging parents to focus on this in the home, because the consequences of not doing so could leave a lifelong impact. I know that this sounds like a huge amount of pressure in your already busy jobs, not least because you don’t just have one child to care for! However, secure relationships are the stepping stones of learning. It also makes your job more fun when you have less tricky behaviour to manage and more enjoyable reciprocal relationships.

Thanks to all Early Years professionals who have worked so hard, particularly in these times of adversity, to remain consistent and nurturing figures for our little ones. You’re support is likely to act as a buffer to the negative impact of the pandemic on children and for that we, as parents, and children will be mightily grateful!