What is happening inside a young child's head? What every early years teacher should know.

The first few years of life are a time of rapid development. And in fact, the first five years are considered to be the most critical in terms of brain development, shaping a child’s future health and happiness.

As I explain in my Parenting Handbook, “Babies are born relying upon the lower part of their brain, which houses their survival system. This means that they don’t have the tools to make sense of their environment and can only show basic responses like crying to express discomfort and thereby get their needs met. Children then start to develop the higher parts of their brain, which are responsible for making sense of their world, and developing some control over how they manage it.”

This can, of course, take time and does not happen in isolation. A child needs input and support from those around them to begin to make healthy connections within the brain.

In their renowned book, The Whole Brain Child, Dr Dan Siegal and Dr Tina Bryson talk about new science that explores how children’s brains are wired and how they mature. In it they discuss the idea of the downstairs brain and the upstairs brain, where the downstairs is primitive and reactive whereas the upstairs is both sophisticated and analytical.

It’s only through time, repetition, and practice that little ones can learn how to rationalise and manage their behaviours and emotions and to take their thoughts and feelings ‘upstairs’. We know that the more we practice things, pathways in the brain are strengthened. But when we don’t they are “pruned”. The brain really does require support to forge healthy connections and grow - we need to “use it or lose it”..

They Have Quite a Lot Going On!

Think about the wealth of different skills your class is developing and you’ll begin to get an idea of the huge range of learning that is going on at this age. From working on relationships and navigating new friendships, to learning to be empathetic, developing a sense of right and wrong and understanding the importance of sharing and taking turns when playing games. They may start to be able to pay attention and concentrate on tasks for longer periods of time, will follow simple rules, and will begin to recognise at a basic level the relationship between action and consequence.

Alongside all of this, other cognitive skills will be developing too. They’ll be learning to count, to recognise and recall the names of things as well as growing their vocabulary at an exponential rate.

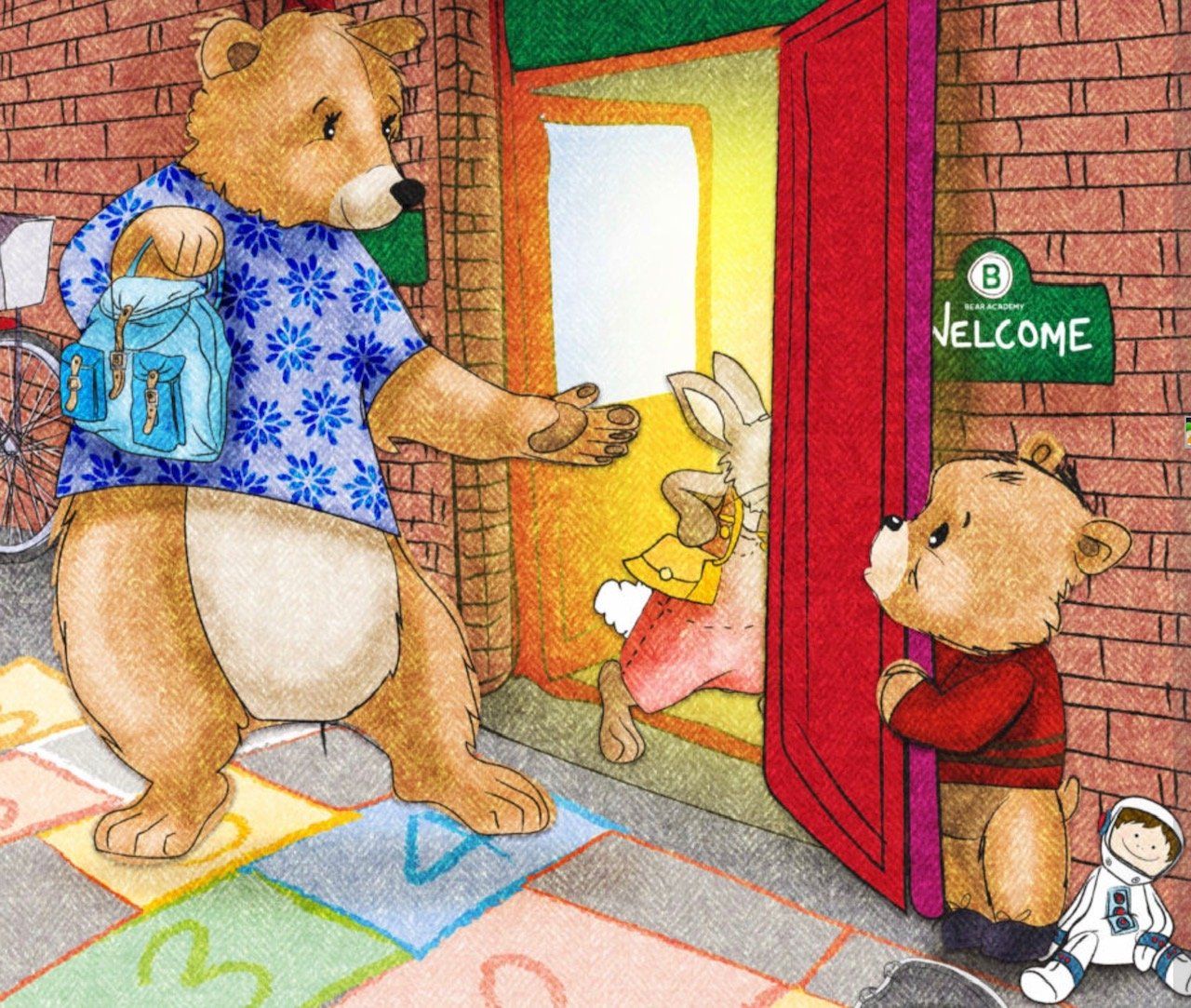

They’ll also be barraged with a range of thoughts and “big” feelings that they are barely equipped to deal with and which they probably don’t understand very well. They’re facing separation from parents and only just starting to understand that words can be used instead of actions in response to frustrations and upset. It makes me feel overwhelmed just thinking about what little ones are contending with (my brain certainly couldn’t keep up!).

At this age, while the necessary skills are being learned, it takes time and repetition to be able to put them into practice. And until then, something that appears to be mastered one day may be forgotten the next; big emotions, hunger, tiredness or difficult relationships may threaten to cause overwhelm and seemingly derail any progress made.

Some Ideas for Early Years Settings

Focus on Relationships

Development and speed of accomplishment of these important skills will depend very much on the experiences children have at home.

What I find fascinating is how key a parent’s response is in shaping a children’s brain development: with consistent and responsive parenting, children develop more healthy connections to the higher, thinking and reasoning parts of their brain. Using these parts of the brain allows children to start to understand and manage their feelings and behaviour.

We must offer a mix of support that allows for social development, cognitive development, communication and language as well as emotional and physical development. But how can we be sure to offer this support in the most effective way?

Perhaps the most fundamental point is that children learn better when they feel they are in a safe and trusting relationship. They need repetition, reminders and patience from the adults around them, despite any frustrations we may feel about the fact they seem to have picked up a new skill and then forgotten it again.

We must expect that there will be successes and failures as they practise new skills and we should offer praise as they begin to remember and master these healthy behaviours. Like any of us there will be good days and bad days.

Ultimately children depend on safe relationships, learning through those around them. If their interactions with caregivers are calm, predictable, clear and available, this puts them in a much better position to develop those valuable skills of emotional regulation. But they need you to co-regulate their feelings first (see previous blog for more information about this).

If you can take a PACE approach children are likely to feel safe and supported with you. This is a model developed by Dan Hughes. When caregivers are Playful, Accepting, Curious and Empathetic children are much more likely to develop secure attachment relationships, and all the benefits that come from this. Have a look at my previous blogs which outline the PACE model in more detail.

Foster Relationships with Parents as well as Children

If you feel children are not receiving the same support at home as they are in the early years setting, it can be difficult to open-up the conversation with parents or guardians, but this is something that is worth broaching. Parents want the best for their children but don’t always have the experience, knowledge and skills that early years staff have.

Talk to parents about the kinds of strategies you’d like to put in place in the preschool/school and whether these are things that might work at home. Perhaps point them in the direction of my Parenting Handbook to help them understand about emotional and behavioural development in young children. Or perhaps you might find tips that are worth sharing with parents through your nursery newsletter or via social media if you feel bite-sized chunks of information are likely to be better received. I’m often posting little tit-bits on my Social Media so do follow and point parents towards my accounts too.

Help Children Understand Their Feelings and Behaviours

Play, play, play and play! Children learn so much through play. Introduce dilemmas, character’s feelings and behaviours when you are playing with children - be led by them but also scaffold their play. This can really help them understand their own feelings as well as expectations around behaviours.

Stories which directly support children with their emotional and behavioural development are also helpful. For example, the first two interactive Bartley’s Books focus upon separation anxiety and tricky behaviours, offering children a platform to make sense of their feelings with the help of a supportive adult. There are more books coming out soon - these help children in the areas of healthy eating, bedtime routines, potty training and the arrival of a new sibling. Watch this space!

Feed the Mind

I love the Healthy Mind Platter as described by Dr Dan Siegal. In it he talks about a neuroscience view of what the brain needs for optimum development - relevant both to children but also throughout adulthood. He explains that we need seven elements, daily, to keep our brain healthy and sharp and to build connections.

These activities include sleep time, something that is particularly important in childhood and adolescence, physical movement time and down time. As well as focus time on an individual project that fosters a feeling of accomplishment, play time to help the brain create new combinations by expanding behaviour beyond the familiar, time ‘in’ reflecting on our inner sensations and connecting time allowing us to give back to others or to the planet.

These activities done regularly and in combination will help our brains to develop long-lasting connections. The Healthy Mind Platter highlights the importance of play and physical movement in our children as well as focussed spells of attention, opportunities for accomplishment, and down time.

Consider how you could introduce a range of these ideas into your days with the children. From physical activity such as music and movement to mindfulness, yoga or children’s meditation, examples of which are freely available on YouTube.

Focus on Social and Emotional learning and the rest will come...

There is so much research to say that the better able we are to manage socially and emotionally, the more able we are to manage everything else that life throws at us. I know I’m a psychologist and I may be a bit biased but I strongly believe that supporting children to develop secure relationships and emotional regulation should be the main (only?) priority of early years settings. After all, when we are feeling anxious or disconnected from others’ its so much harder to explore the world with curiosity and learn.

There’s so much we can be doing for our own little ones, whether that’s through supporting parents or within a classroom setting to improve their chances of a happy, healthy and satisfying future.

For those of you working in early years I hope you realise how important you are in shaping children’s futures. They way you, as a profession, have shown your commitment to young children in your care over the pandemic has been inspirational. Thank you!