Attachment explained – what it is, why is it important and how you help your child to become more secure

“Attachment is as central to the developing child as eating and breathing”. (Robert Shaw)

This blog addresses these questions and focuses upon ways that parents and educational settings can put attachment theory into practice. It is based upon my experience as a Clinical Psychologist. For over 15 years I have been drawing upon attachment theory to inform my work with parents and children.

I’ve tried to ensure that my suggestions are user-friendly. As a mum of three I have learnt that theory does not always feel that easy to translate into practice. We can feel pressured to get it right all of the time (apologies to the clients I worked with before having my own children!). The beauty of attachment theory is that we don’t have to be perfect. Just good enough.

As with anything scientific there can be a lot of jargon – I have put the key words in italics and tried to write with minimal psychobabble. I do hope you enjoy it!

What is attachment (in a nutshell)?

Attachment theory was developed by Psychiatrist John Bowlby in the 1930s.

Depending on the experiences a child has with their parents, and other important adults in their life, they develop certain ways to respond to others and view themselves and the world. Shaped by their experiences of being parented, children develop an internal working model, a template of how they see themselves and the world which is. It’s quite clever really – humans learn to behave in the way that will help maximise their chances of getting their needs met.

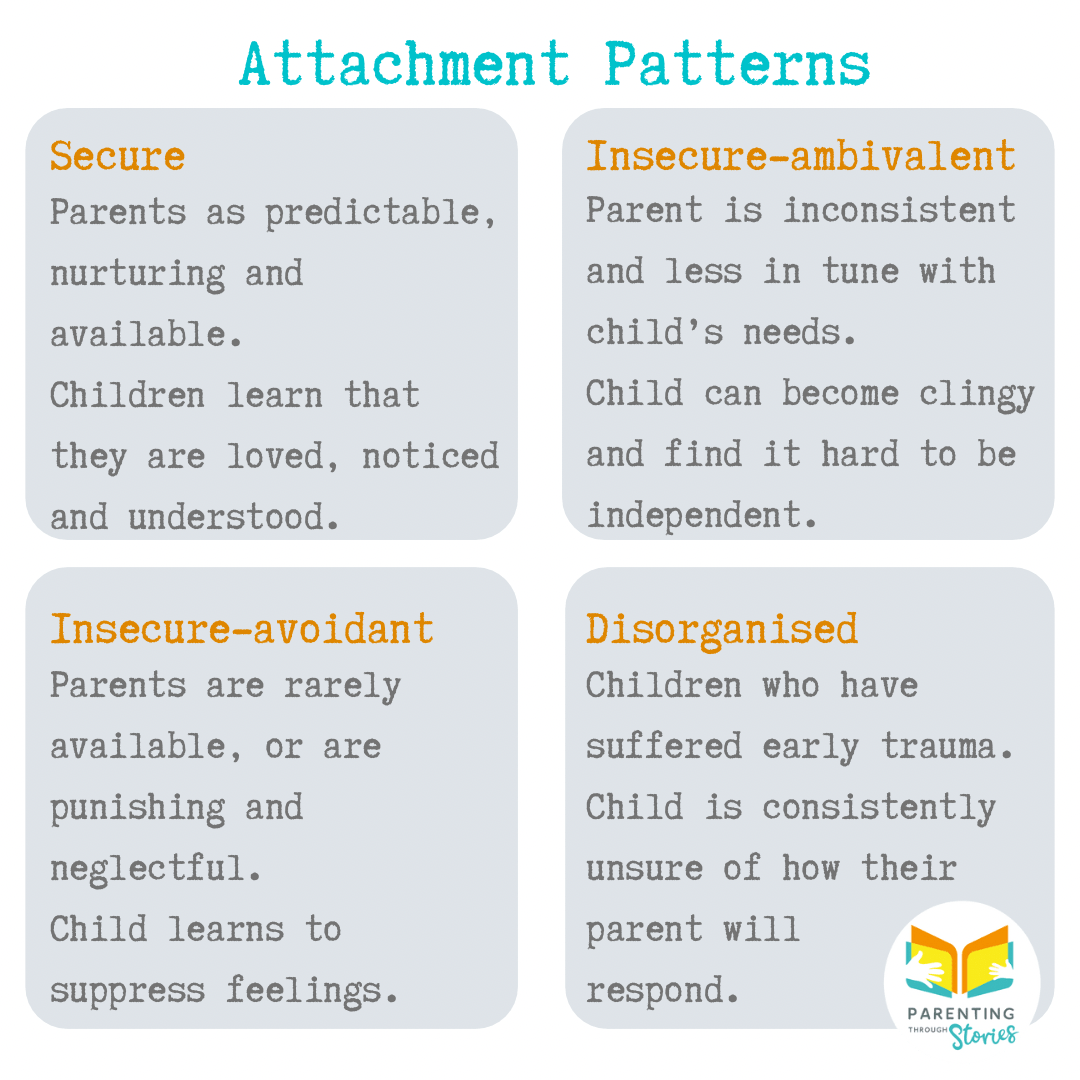

How do different types of parenting relate to different attachment patterns?

Research has shown that there are four different patterns of emotional expression and behaviour that children develop according to the parenting they receive. These come out when they are under stress, being shown through how they use their parent to help them cope with this.

Secure attachment

Around 60% of us develop a secure attachment. This is when children experience their parents as predictable, nurturing and available. Children learn that they are loved, noticed and understood.

Children develop secure attachment relationships when their parent is in tune with them. When they notice how they are feeling and behaving and help them make sense of this (known in the trade as attunement).

.

Insecure-ambivalent attachment

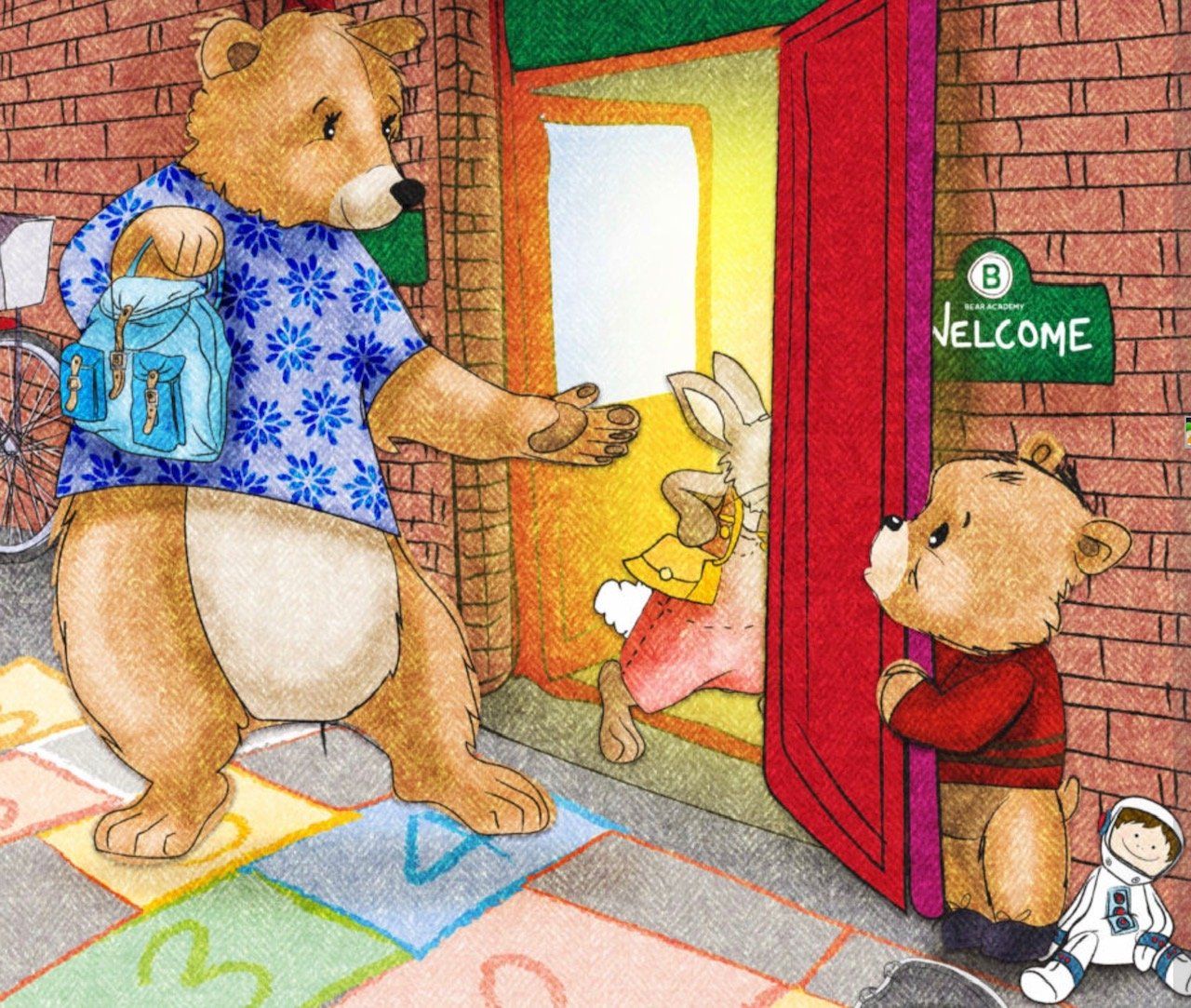

We also talk about insecure attachment relationships. These develop when a parent is less in tune with their child’s needs. If a parent is inconsistent – sometimes available and sometimes not – they are more likely to develop ambivalent attachment relationships. Children learn that they are more likely to get their needs met if they stay close to their parent and can become clingy and find it hard to be independent. They are often led by their feelings and have a fear of separation.

Insecure-avoidant attachment

Children who have parents who are rarely available, or are punishing and neglectful, can learn to suppress their feelings and not ask for help when they need it. They develop avoidant attachment relationships. They are often too independent, scared of being rejected and led more by their thoughts rather than feelings.

Disorganised attachment

When children are exposed to very frightening care-giving they can develop disorganised attachment relationships. This is what I often see in my clinical work, with children who have suffered early trauma. Sadly, this leaves a child consistently unsure of how their parent will respond – they don’t know what to do as their supposed source of comfort is actually a source of fear.

Don’t panic!

At this stage you may be panicking – asking yourself if your child is secure enough, berating yourself for not being available as much as you could have. Try to remember that secure attachment relationships may be what we aspire to, but they are not actually that normal! Please try not to worry - nearly half of us lean towards insecure attachment relationships - they are adaptive ways to fit with the parenting that we have experienced.

We all have strengths and struggles.

Of my three children one has a tendency towards avoidance, the other ambivalence and the other security…and that’s OK! When I think about it it’s pretty obvious how my parenting has led to them coping in different ways. We need to notice our foibles (as well as those of our children) and think about what changes we might need to focus on.

Focus on being good enough, not perfect.

The other thing to remember is that no one is available and nurturing all the time – it’s not humanly possible. A recent study on infant attachment found that parents need to be “in tune” with their babies about 50% of the time in order to develop secure attachment relationships (Woodhouse et al., 2019). Try not to worry too much if you feel like you are getting it wrong more than you would like to.

Remember some behaviour is developmentally normal (and not a sign of insecure attachment).

For those of you with little ones you may also be thinking about your toddler’s behaviour – they may have become very clingy or overly independent (or oscillate between the two). This is normal! They are starting to explore the big wide world, wanting to do things on their own, but not always being able to do so. Meltdowns, separation anxiety and having to put on their own shoes are all par for the course, however frustrating!

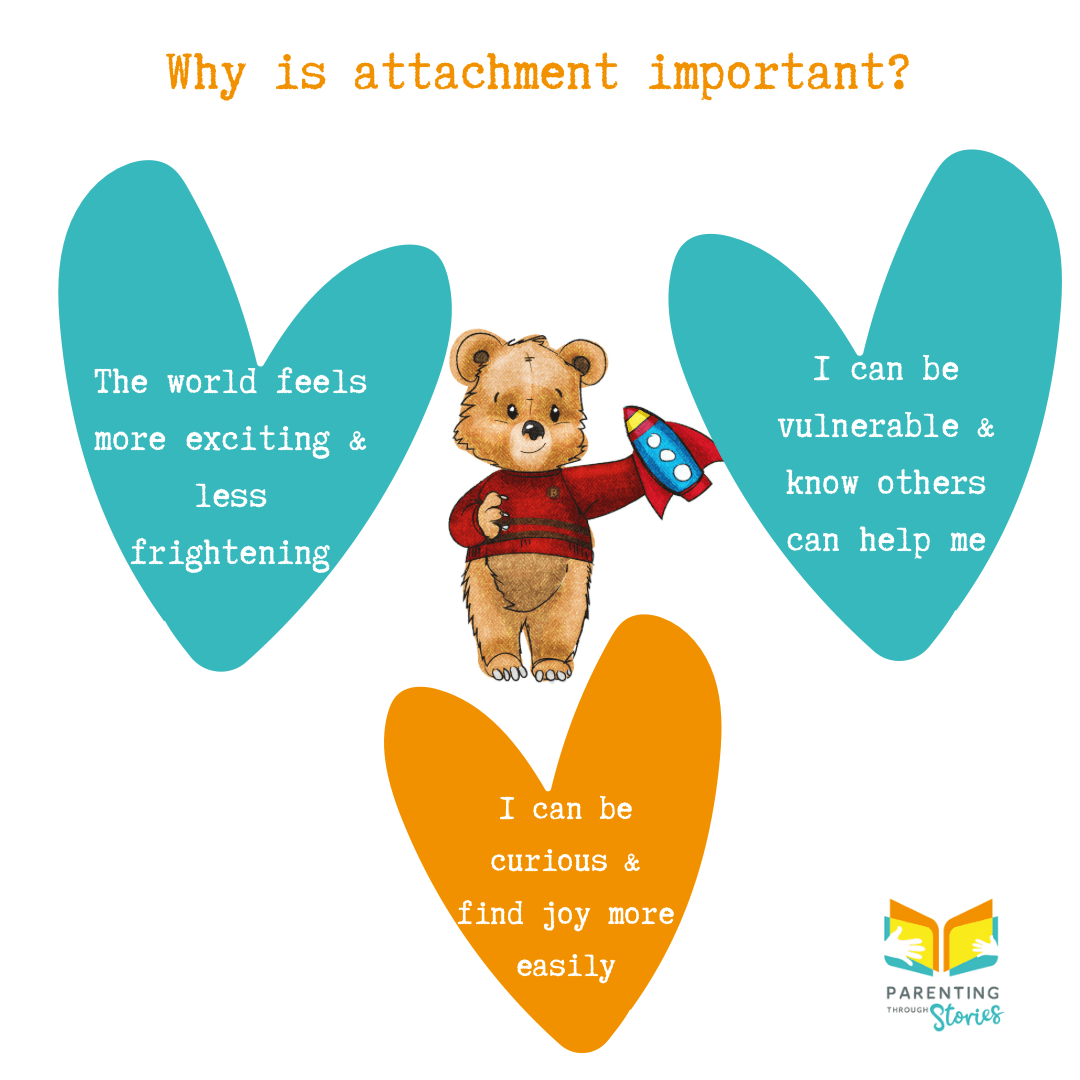

Why is attachment important?

The benefits of developing a secure attachment are multitude - when we are safe in our relationships the world feels more exciting and less frightening. We can be vulnerable and know that others can help us, we can be curious and find joy more easily.

Our internal working models are shaped into believing we are worthy and loveable and that we can influence others. We approach the world accordingly. When things get too much, we know that we have a “safe base” to return to for help (have a look into the circle of security if you want to know more - https://vimeo.com/circleofsecurity).

Just through picturing your child’s last tantrum you will well know that, when we are little, we struggle to control our feelings and behaviour on our own (known as self-regulation). However, through co-regulation (where an adult helps a child learn what they are feeling and manage their feelings before they can do it for themselves) this happens more quickly. Not surprisingly, it is through secure attachment relationships that co-regulation works best. See our previous blog on co-regulation.

And if that wasn’t enough, there is evidence that secure attachment results in optimal brain development, the development of self-awareness and empathy, better friendships, more engagement and success in learning and better problem solving…the list goes on!

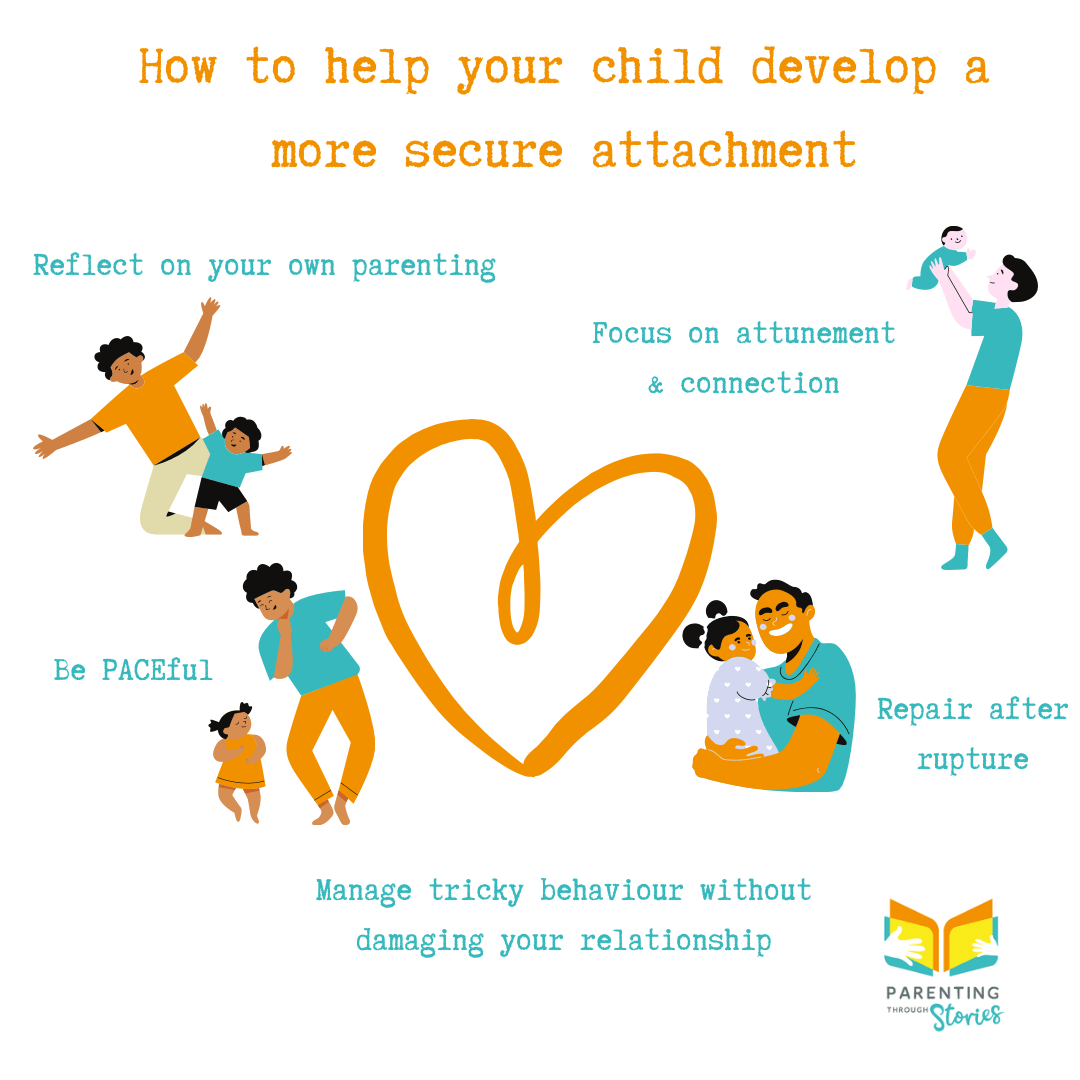

How can you help your child become more securely attached?

There are lots of ways that you can help your child become more securely attached to you - it’s never too late!

Reflect on your own parenting

Just like our children, we also have internal working models that are established early on and have developed from our experiences of being parented. These come out to play (often unconsciously) in our own parenting behaviour. Interestingly the most significant predictor of a child developing a secure attachment is their parents’ ability to mentalise (the ability to understand our own, and others, minds).

The first thing to do is think about yourself, ask yourself the following:

· Where do your strengths and vulnerabilities lie as a parent?

· Do you tend to dismiss emotions?

· Are you somewhat inconsistent in your parenting?

· What did you learn from your parents? How did they support you to feel safe and learn to manage your feelings and behaviours?

· Are you more driven by feelings or thoughts?

· How does this translate into understanding and meeting your child’s needs?

If you were part of a “just get on with it” family you may be more likely to dismiss your child’s feelings and expect them to cope on their own (leading to more avoidant ways of coping). If your parents were more available, but inconsistently so, your child may start to become more ambivalent.

Before you start worrying about your ability to change these patterns it’s important to remember that, even if you had a very difficult childhood you can still develop secure attachment relationships with your children. It just may take more support and reflection.

Focus on attunement and connection

Next, make sure you spend time noticing your child and trying to work out what are they showing. Sometimes what they express they need is different to what they actually need! Helping your child understand what is going on for them and storying this is also really important.

Try to ensure you have some time together that is about being with each other, not just doing (easier said than done with such busy schedules). Connected moments where you are influencing each other are known as intersubjective experiences. My son’s nanny always reminds me of how important this is – spending a day a week with my son without an agenda and with lots of moments of connection. It is so good for him (and her). It may sound simple – just try to enjoy each other as much as you can.

Be PACEful

Developed by Clinical Psychologist, Dr Dan Hughes, the PACE approach has been developed to help children develop more secure attachment relationships. It involves taking an attitude of Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy in your parenting. Have a look at our blogs to read more on each of these elements. More about PACE can be found in my Parenting Handbook and the approach is also embedded into my interactive picture books - Bartley’s Books. (As you may be able to tell, I love this model!).

Manage tricky behaviour without damaging your relationship

When things get tricky it’s important that you try to manage the behaviour whilst also showing that you love your child unconditionally. You may disapprove of them drawing all over the walls, but that doesn’t mean that you have stopped loving them (even though you may not feel the love at that time!).

Young children need to learn that what they have done is unhelpful, and find other ways to behave, rather than that they are bad. Discipline is about teaching, not punishment, and the more secure they feel in your relationship the more they will let you influence them. Connect with them before you correct the behaviour – this helps both your attachment relationship but also their behavioural development.

Clinical Psychologist Kim Golding talks about the need to connect before you correct, as do Dan Siegel and Tina Payne-Bryson. You can also find a step-by-step guide to managing tricky behaviour without getting in the way of your relationship in my Parenting Handbook.

Repair after a rupture

We need to make mistakes and have ruptures in our relationships to reconnect and deepen that attachment security (we call this rupture and repair). So, when you do get it wrong give yourself a pat on the back and think of it as a chance to get closer to your child and show them that we all mistakes. (If you feel you are really struggling though then do ask for help).

As you may have gathered, I could talk about attachment until the cows come home! I’ve introduced lots of ideas today and left a huge amount out. You can hear more about many of these ideas in my Parenting Handbook and I’ll happily write more blog articles on areas you would like me to explore further – just let me know what these are.

I would also recommend having a look at The Power of Showing Up by Dan Siegel and Tina Payne-Bryson which looks at attachment and brain research and provides lots of really simple ideas to help your child feel more secure.