The Bear Necessities of Life: the ‘im-paw-tance’ of Bartley being a Bear

Parenting Through Stories • 16 February 2020

Whether kind and caring like Pooh, quirky and cuddly like Paddington, or loyal and, well, a little lairy like Iorek, bears’ paw prints can be found across the gamut of children’s literature.

So, just what is it about bear characters that captures readers’ imaginations?

And how does Bartley Bear and his family transcend the literary trope?

Bearing With It

Bartley wasn’t always a bear! Sarah and Rachel experimented with various incarnations of the young male who would be at the centre of Parenting Through Stories.

It was important is that he wasn’t human - as it’s the alternate, fictive world that Bartley inhabits that allows the child reading the story to experience his feelings, and reflect on their own, from a comfortable emotional distance.

So, why did they settle on a bear?

As far as anthropomorphised animals go, bears have got it pretty good.

Mice = meek.

Lions = a little aloof.

Wolves = big, bad.

Bears = Honey-loving, strong and large-hearted…whilst they’re not always book-smart, they almost always have a high EQ.

Their narrative function is often as teacher - see Kipling’s Baloo - or mentor…note the low-key manner in which self-effacing Pooh imparts important life-lessons.

I personally appreciate the anti-establishment antics of Yogi-bear. Whilst teddy bears’ penchant for picnics has been well documented, Yogi’s obsession is next level. Wait for it…Yogi puts the ‘nick’ in picnic. (Sorry, couldn’t resist).

Depicted in varying degrees of humanness, the matted fur of bears' uncouth antecedents is typically sloughed off in stories in favour of sassy sartorial swagger: Yogi sports a dapper trilby, Rupert some pretty snazzy slacks. But it has to be Paddington who takes the sandwich (marmalade, of course). His yellow-boots and red-mac combo is as iconic as any Chanel ensemble.

Given these literary ‘paw-fathers’, it’s no surprise that the inquisitive, cheeky and playful characteristics of Bartley are well-suited to bear DNA.

Grin and Bear It

One of my earliest memories is of my fourth birthday. We had a surprise guest. The Birthday Bear.

Now, on an estate in the north of England in the summer of ’85, this was a pretty big deal. I mean, the grizzliest thing we’d experienced to date was either when Little Jack smashed Mr Dontbreathenearmycar’s front window during a particularly brutal game of rounders, or that Saturday the ice-cream man ran out of flakes. Gruesome scenes, both.

I was four and, given that I believed dragons lived in the nearby woods (Ig, Og and Ug, as you’re asking), a huge brown bear attending my party was accepted without question.

Full disclosure: our family was an anachronism on the estate. Both of my parents worked (!), I didn’t wear make-up (!!) and did wear dungarees (!!!). We were definitely odder, if not odd-balls. And, now, I thank goodness for it.

Then though, I worried about not being, well, a little more beige. I watched only limited TV, so my references were not like the other kids…social events were often nerve-wracking emotional ricochets between confusion, misunderstanding and shyness.

When the Birthday Bear showed up, amidst the sheer awesomeness - a bear! - a small part of me worried that the other kids might not like him and therefore me by extension.

(Although, really, exactly what did I imagine their beef with him to be: “Oh my goodness, does that bear even own a crimping iron?” “And where is his shell-suit?” Such is the ridiculousness of overly concerning yourself with others’ opinions.) M

My fears of course were unfounded: a four year-old’s social calendar is relatively tame. You can bet no other kid had a bloody great grizzly bear helping her blow out her candles.

The Birthday Bear caused some general mayhem, chased us around the back garden, bundled us into some bear hugs then loped off back to the woods at the end of the cul-de-sac.

(The only thing that was a little perturbing was that the bear had taken a fancy to my dad’s trainers…he wore them the whole afternoon. Curious.)

I still remember that bear hug. It felt reassuring; it felt like home.

Hug from the Heart

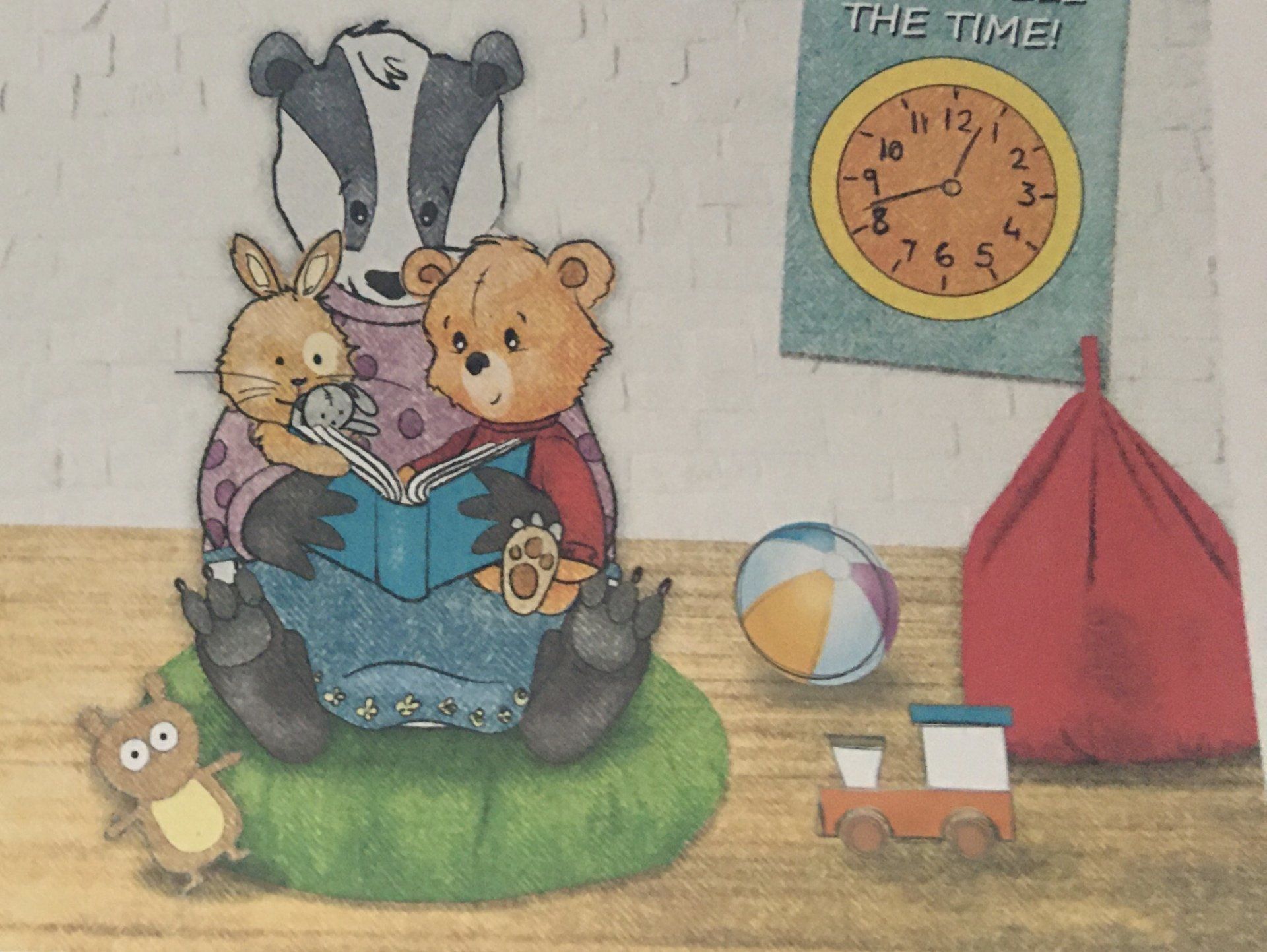

Whilst I wouldn’t recommend seeking one out in the woods of Wisconsin (real bears don’t ‘hug’ unless they’re making you their picnic), the bear hug - as co-opted by humans - is something all parents have in their toolkit…and the concept is key to Bartley’s Books.

Fathomless, warm and accepting, Bartley’s parent’s arms are always there as a safe space: as a touch-stone when he’s feeling happy, or sad, or stressed.

A vital part of the parenting approach we’ve been discussing is the connection you forge and strengthen with your littles. Even if it’s not as a result of a ‘rupture’, a cuddle re-affirms your bond - as does the physical closeness you have when you’re reading together.

However, the bear hug as a metaphor is even more powerful.

One of our key roles, we’d all agree, is trying to inculcate a deep feeling of security in our children. Our arms will not always be there to shield them from the world, to sooth their anger, or soak up their tears. But, the emotional resilience we can foster for them, now, through our parenting actions, can be.

Through PACE, active reparation when things go awry and a reflective approach to parenting - and living in general - we can call into being an embrace that defies physical limitations.

Their belief that they are accepted, that they are safe and that they are loved is a portable cuddle they will always carry with them.

As I said, I can still feel that hug: it thwarts time, and cheats death.

Bear it all

For all of the above, do you know the best thing about bears?

They are wild.

What I love about how Sarah has written - and Rachel has depicted - Bartley is to emphasise this sense of his inner freedom…

His imagination runs wild.

He is unfettered by pesky reality: he jets off into space; he IS an astronaut.

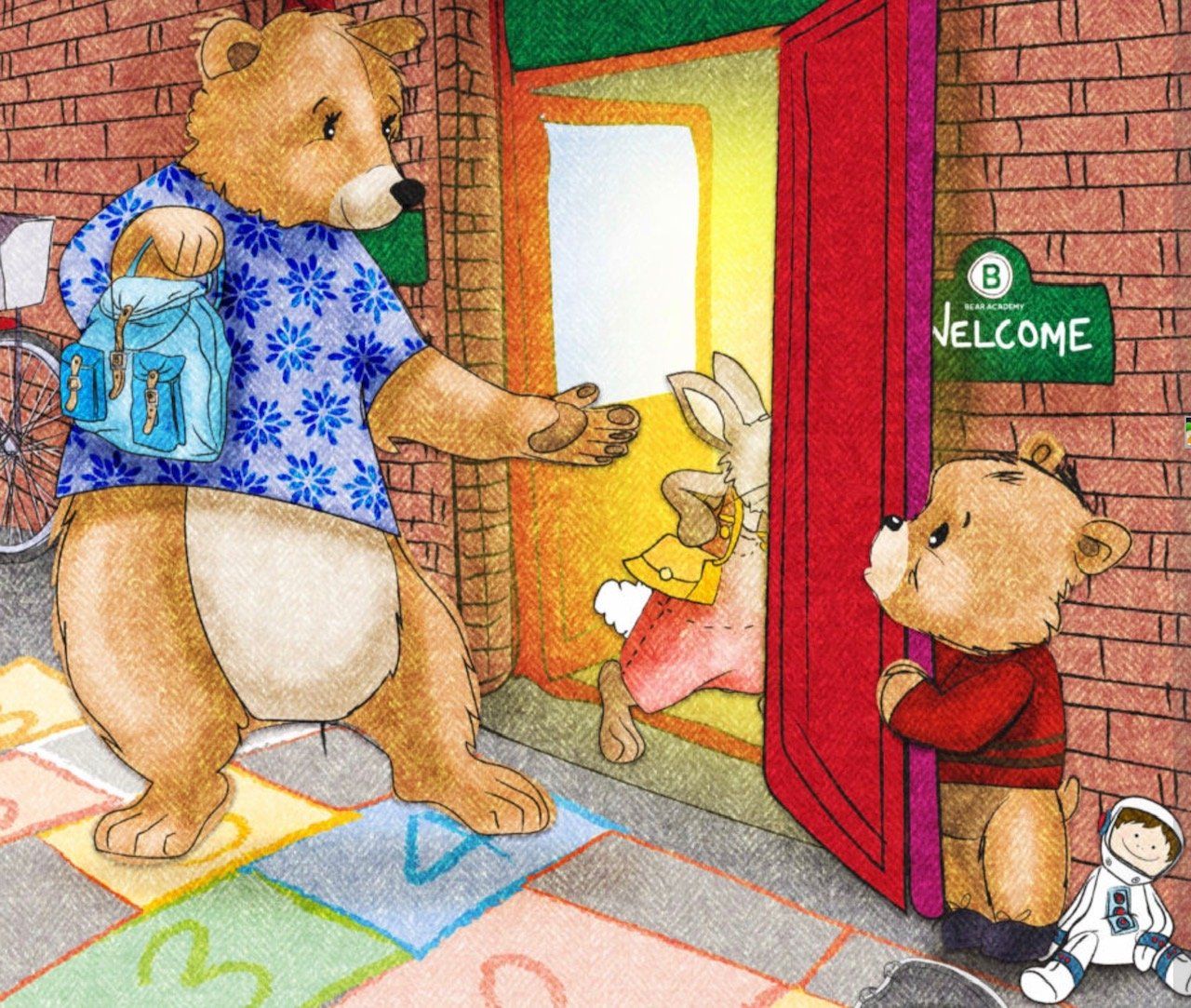

His mum capitalises on this, using creative means to get Bartley out of the door and down the street to school with a huge grin on his furry face.

Of course, Bartley represents our own cubs whose vivacity and wildness we celebrate and delight in; whose imagination we know we have lost and are poorer for it.

Exit, pursued by a bear

Last week I suggested we should be more Elsa…this week I’m ending with a similar call to arms (or paws).

The things that will impinge on our kids’ future freedoms might be physical, but are much more likely to be internally constructed barriers.

The world has room to make a bear feel free;

The universe seems cramped to you and me.

Man acts more like the poor bear in a cage,

That all day fights a nervous inward rage. (Frost, from The Bear Poem)

As Frost describes it - the ‘nervous inward rage’ cages our adult selves, limiting our potential.

We are frequently our own jailers. However, even from within our own prisons, we can set our kids free.

Right now, in their childhood, we can bestow upon them the keys (or cudgels) to unlock (or break down) the psychological walls that could encage them.

And we can do this through PACE parenting, reparation and reflection and lots of talk-time with our tots.

So, think of Bartley and his ‘bearishness’ as totem or spirit animal…and be more bear:

• Hug your cubs long and hard.

• Through conscious PACE parenting, set them free: physically and emotionally.

• And, of course, grab a marmalade sandwich, some honey for tea and go on a picnic with your little teddy bears.

These really are the bear necessities of life.

x Becks

We’re within four weeks of the Crowdfunder campaign beginning. Follow our journey on the channels below and keep sharing your stories about PACE parenting and the importance of story-telling.

“Playing with our kids and really getting to know them is a little like scuba diving. From above the surface of the water, it’s hard to know what’s really happening down there under the waves. But when you take the plunge, you discover this whole other world: dynamic, real, fascinating, beautiful and full of life” (page 5) Why is play important? · Play is in children’s nature – it’s their first language and helps them learn with creativity, joy and connection · It builds crucial skills and reduces unwanted behaviours. Children build confidence, resilience and self-understanding through play. And with this comes a reduction in fighting, rudeness and tantrums (a reduction not an extinction – these are all part and parcel of childhood!) · It gives children appropriate ways to express and process their emotions and can be a powerful way to process what has happened and heal after difficult experiences. · It can help us connect with our children and enjoy being with them. It helps us understand their inner world and delight in them, building their self-esteem What if we don’t know how to play? (something I hear from lots of parents) · If we struggle to play it’s not our fault – our brains grow and change since we were children. · We have to relearn what it means to think and play like a child · For those of us who haven’t had playful parents when we were growing up it may be harder – but it’s never too late to learn What are the strategies that the authors talk about? This is a very brief summary – it’s well worth reading the book for a full exploration with lovely illustrations, example and science behind the strategies. · Think Out Loud o Why? This helps children understand their thoughts, feelings, wishes, intentions and desires more. When we do this it helps them learn that others can understand them and help them understand themselves. We help children to pay attention to what is happening inside themselves so they can develop positive, conscious, international responses rather than the default reaction with no awareness! o How? We do this by observing and narrating what we see in our children’s play, commenting on mental and emotional stages. We do this by observing and attuning, coming up with a hypothesis, saying it out loud (don’t worry if your guess is wrong – your child normally lets you know!) · Make Yourself a Mirror o Why: help children understand their emotional life and enhance their connection with and empathy for others. o How do we help children exercise the empathy muscle? (love this term!). Observe and attune into what your child is feeling with your body, face and voice, activate your child’s mirror system and remember empathy is mainly conveyed non-verbally (as well as verbally) · Bring Emotions to Life o Why: help children recognise, manage and express feelings. o How: observe and attune (as you may have noticed, we always start with this!) watching for emotional cues, act out your part adding emotions to your character (if your child invites you into their play) – alternatively, touch on emotions as the narrator of their play. · Dial Intensity Up or Down (this feels more about general parenting that play) o Why: this helps children regulate their emotions and actions when they are struggling and helps them learn that someone will be there for the when out of control. o How: Observe and attune – looking out for your child becoming dysregulated. Chase the why (I love this phrase) – see if you can work out what their dysregulation may be about? Look beyond the behaviour (if you want to learn more about this read Mona Delahooke’s work – it’s brilliant!). Dial the intensity up (through cooling things off ) or down (through starting low and going slow) Regulate and repair o Scaffold and Stretch: Why? Help children learn resilience in the face of difficult situations and show them others can show up when things get hard. How? This is about helping your child face something difficult in a low stakes way – through play. Firstly, observe and attune – to see if they may benefit from some support. Then offer scaffolding and stretching – it’s getting the balance right between not taking over when there’s a little struggle (my tendency!) and not letting them struggle so much they get stressed and don’t learn… Narrate to Integrate · Why? using stories (obviously my favourite thing!) to help children understand and deal with difficult situations. · How? Observe and attune (did you guess that?!), oscillate (between different halves of the brain – use logic and emotions), integrate and elevate. Set Playtime Parameters Why: boundaries teach children how to make positive decisions and help them feel safer. Children need limits, connection, structure and nurture How? Set some rules for play by taking care of yourself and of the space (try not to make it too chaotic!). Remember you are the pit crew not the race engineer (!). If you’ve had to set a limit then acknowledge the desire but keep the limit and offer alternatives. The authors set some good ideas for transition tips (as transition out of play can be HARD!). Finally, Tina and Georgie end with the importance of being playful outside of the playroom. For those of you that have read my parenting handbook and know about my love about the PACE model you’ll have guessed that I was pleased to see this in! Overall, a great read…well worth a delve

Little children can be so confusing (and confused!). Sometimes it’s hard to know what they need from you - a three-year-old demands that she wants her cheese in a big piece one day and then cries because it’s not cut up the next. She wants you to hold her hand to go to the toilet in the morning, but later gets cross when you try to do the same. We’ve all been there, faced with the - sometimes baffling - behaviours of the small humans that surround us, wondering how to respond to their inconsistent requests. Perhaps it’s reassuring to realise that these seemingly random behaviours are actually quite natural - stages through which each child progresses. In a bid to help you support your growing pre-schoolers more effectively, this blog talks about some of the things (there are many!) happening inside their heads and how you can support them with what’s going on. What’s Happening Inside a Three-Year-Old’s Brain?

What was your favourite story when you were growing up? Was it a traditional fairy tale like Cinderella? Was it a popular picture book like The Very Hungry Caterpillar or The Gruffalo? Or was it a great adventure story like CS Lewis’ Narnia series or JK Rowling’s Harry Potter? Mine was Dogger by Shirley Hughes. Funny that the first book I wrote was about separation anxiety! For many of us, sharing and reading books was an important part of childhood, even more so before the advent of distracting screens and 24/7 streaming. I have fond memories of curling up in bed, half asleep, as my mum or dad read to me complete with silly voices and giggles aplenty. It's not just books though - you can make your own stories up too. I tell my little one a story about “Grizzly Bear with the Curly Hair” every night. It’s evolved to be a lovely family tradition, with my older children sometimes coming to join in. This is a wonderful way to stimulate both mine and my children’s imagination and what I most love about it is how the narrative is co-constructed – I am no longer allowed to be the sole story-teller, my son has to be part of it too! A 2018 research study found that nowadays only 30% of parents read to their children daily and I can’t help feeling that’s a bit sad. Especially given the many benefits of sharing story time go far beyond pure entertainment.

I thought I’d do a post on guilt and shame, feelings which are often used interchangeably but, from my understanding are pretty different. A quick whizz through some child development When we are little, particularly when we start testing the boundaries during toddlerhood, parents need to intervene to keep children safe. For those of you with little ones the word “NO” probably comes out more than you would like it to! This is a normal part of development – children exploring without an understanding of risks, and needing adult involvement to know when to stop. When a child is asked to stop doing something, which was most probably led by curiosity (can I touch that hot thing in the fire place?!), they are likely to experience shame. It’s not a nice feeling but is quickly regulated when a parent explains their motive and repairs the rupture in the relationship. “I’m sorry that I raised my voice, I know you were just exploring but it’s dangerous to touch fires” and so on. This gives the message that the parent is still there for the child and that they are accepted for who they are. The parent is showing them that their behaviour not OK, but that they are. This sort of parenting, when reasonably consistent, leads to a child feeling guilt rather than shame. “Oops, I shouldn’t have done that, how can I make amends?” (obviously not so clearly thought out for little ones but you get the gist). .

As a newborn, we look to our parents for everything. To feed us, to comfort us and to protect us. If they give us this safety and security, a healthy emotional bond develops. Research shows that this attachment relationship is a crucial building block of a child’s development, helping them to grow socially, emotionally, behaviourally and intellectually. But what happens when children begin to spend time with other caregivers, outside of the home and away from their parents? Do they develop similar relationships with the nursery staff, childminders or pre-school teachers that look after them? And what does this mean for you if you’re working in Early Years?

If you work in an early years setting, you’ll be quite familiar with the scene. You’re welcoming the children and getting them settled at the start of the day, checking in with them and showing them what activities you have planned. Suddenly, you hear shouting and crying as a stressed-looking mum tries to detach her small child from her leg. You feel for her, you really do; this child regularly clings to her on arrival - the anxiety is palpable. It’s distressing for everyone involved. For Mum, for the child, for the other children who are already in the room, and not least for you. You know from experience that they will settle down and be OK, but that doesn’t make it any easier in the moment. And you know, too, that poor Mum has headed off to work feeling guilty and upset, so it’s unsurprising when she phones 15 minutes later seeking reassurance from you. These experience are likely to be more pronounced at the moment, with children having fewer, if any, opportunities to practice separating from their parents, with collective anxiety at a huge level and with normal settling in sessions, with parents in the room, being unavailable. What is separation anxiety?

Where do I start? Attachment is a HUGE topic, with decades of research highlighting how important it is to a child’s development. But do you know what an attachment relationship actually is? And why it’s so important? Do you know what helps children develop more secure attachment relationships? With different approaches and a number of terms banded around it can feel so confusing. This blog addresses these questions and focuses upon ways that parents and educational settings can put attachment theory into practice. It is based upon my experience as a Clinical Psychologist. For over 15 years I have been drawing upon attachment theory to inform my work with parents and children. I’ve tried to ensure that my suggestions are user-friendly. As a mum of three I have learnt that theory does not always feel that easy to translate into practice. We can feel pressured to get it right all of the time (apologies to the clients I worked with before having my own children!). The beauty of attachment theory is that we don’t have to be perfect. Just good enough. As with anything scientific there can be a lot of jargon – I have put the key words in italics and tried to write with minimal psychobabble. I do hope you enjoy it! What is attachment (in a nutshell)?

In case you hadn’t noticed, Christmas is coming, and fast! It’s different this year, without nativity plays, big get togethers and light turn-ons. But it’s still happening, as both we, and our children well know! My three-year-old is already telling me that it is “Christmas tomorrow” on a daily basis (to be fair he also thinks it’s still Halloween so he’s not particularly accurate in his understanding of seasonal activities!). He is, however, starting to get excited. He’s remembering the elves escapades from last year, asking when they are coming back (I still haven’t found them in my cluttered house!). Why I added the nightly task of creating funny Elf scenes throughout December to the already huge list of Christmas jobs is beyond me, but at least he likes it! I was also quite proud of last year’s zip wire adventure.

I know the gold standard for writing blogs is to deliver them on a fortnightly basis. I’ve been a bit remiss as this is my first one in months! What a better topic to start with then than why it is OK not to get things right all the time. Perfection is unobtainable, but it does seem to be something that we are pushed to do. The number of posts out there on mum guilt is astonishing. Over the last year we have been expected to juggle life in a way that does not seem possible. Many of us have been coping with (or trying to) being teachers, parents and professionals, three full time jobs all at the same time! This has left me wondering whether it’s actually possible to do anything well enough! And then along comes Christmas (gulp!). I’m hoping that reading this will leave you feeling happier with how you are doing as a parent, that you will realise that buying into the pressure to get it “right” is not helpful, and that you will learn that the attachment research highlights how we don’t need to be perfect to raise happy and healthy children. Children don’t need us all of the time. They need is a parent who knows they are good enough for them, accepts their foibles, makes and owns mistakes, and can manage their own emotional world. Forget Perfection - Strive for Good Enough Parents can feel a great deal of guilt around their work/life balance. Guilt can actually be a helpful emotion, allowing you to reflect on what is, and isn’t working. However, when you have little control over the things you want to change, it can feel overwhelming. The first thing you need to remember is that you are doing your best, and that is good enough. Interestingly, an article in the Economist reported that we spend twice as much time with our children as parents did 50 years ago (The Economist, November 27th 2017), suggesting that we are already much more active in our parenting than we used to be. “Good enough” is key to parenting. Research into attachment, which is important to children’s development, highlights how we should strive to be good enough, not perfect. A recent study on infant attachment found that parents need to be “in tune” with their babies about 50% of the time in order to develop secure attachment relationships (Woodhouse et al., 2019). So, if you’re getting it right about half the time, you’re onto something! Quality of Time is Far More Important than Quantity

Well what a year it has been. Not one that any of us could have imagined or would have hoped for. All over the world we are having to adapt to the threat of Covid-19 and uncertainty about the future. Children have had prolonged periods away from education and, although some of them are back, this can be on and off as and when Covid-19 dictates. Helping children cope with these changes is key for the education sector if we are to support them to re-engage in learning. As a Clinical Psychologist I have been working with schools as well as children and families over this difficult period. I wrote this blog to summarise some of the ways educational professionals can support children through the increased anxiety they are likely to be feeling. Anxiety and Covid-19 A global pandemic is not good for anyone’s emotional wellbeing and is having an impact upon us all. Whilst we are all in very different situations, it is far from what any of us are used to and children will be noticing these changes. They are likely to be seeing more worried adults, hearing more stressful news and having little, if any, time with friends. Children have had to contend with new rules, a change in routine, a lack of control and a loss of relationships. Like us, they feel safe when things are predictable – something which has been absent for many months now.