I’m Sorry, I Haven’t a Clue: why fallibility is our parenting super-power

Parenting Through Stories • 2 February 2020

There are many mysteries in parenting: some destined to remain so and others to be solved along the way.

How will we get him to potty train?

Will she ever sleep through?

What happens to all the socks?

Exactly how much Paw Patrol is too much Paw Patrol?

And just why does Pando only wear pants?

Whether large or small, the questions that arise as we nurture littles into bigs can often be over-whelming. It’s no wonder that on occasion, our solutions are more miscalculations than marvels. And often, we’re a part of the problem.

Now. This blog is not about beating ourselves up…we’re all going to make mistakes. I do. You do. I do again. By the minute, sometimes.

As we’re so good at telling our kids, mistakes are fine as long as you try and learn from them. We seem to forget this, in adulthood. Whenever that begins.

I’ve seen emblazoned on many a supermarket T-shirt: ‘My Mum’s / Dad’s a super-hero’.

Standing there, milk-sodden and snack-covered, contemplating crying baby and whining toddler,

the heroic parenting figure it refers to - glossy mum? baby-wearing dad? - feels far from that aisle of woe.

‘My Mum’s / Dad’s a super-hero’.

Is there not a certain sneering, even boasting tone about the sentence. A taunt? Judgement, even?

‘Well, good for you,’ I’d hiss back, hiding the offensive blighter with a onesie - a famously far less bolshy item - and scurrying off, before the trousers joined in.

Heroic Fails

Amidst the shock and awesomeness of those first few months, then the years of sleep deprivation and only the total realignment of your identity, the idea that parents can be perfect decision-makers, infallible super-heroes, is, frankly, bonkers.

Plus, super-heroes wear their pants outside their leggings, which is daft and something I’ve only done once after basically no sleep and absolutely no-one mistook me for a super-hero, unless my super-power was to call forth pitying looks and terribly hidden sniggers…

I get that we’re fab jugglers, performing super-human physical feats (car-seat wrestling, anyone?) as well as listening, cooking, cleaning, wiping and frequently listen-cook-clean-wiping…

But we’re also HUMAN.

Thankfully, our humanity is the point.

We need to grab hold of it - in all its messy, fallible, bodge-job-on-occasion gloriousness - and show it to our kids. We need to model that being imperfect is normal…and also map out what to do when we realise we’ve fallen short of the ‘hero’ standards we (perhaps stupidly) set for ourselves.

A large part of the approach Sarah advocates is around reparation: making things better when it all goes wrong, feelings are hurt and relationships stretched or frayed. Making mistakes, of course, but acknowledging them and repairing the relationship effectively afterwards.

Paradoxically, it’s our natural, non-heroic normality that can be turned into our parenting super pow-er.

‘I’m Sorry’ - is that all that you can say?

Sorry is a powerful word - and it’s important. But whilst it might be a brief salve, the wound it seeks to repair lies much deeper.

If we see sorry as a sticking plaster covering maybe the more obvious emotional wounds (crying, for example), the real act of repairing a relationship is from the inside out…healing the hurt, confusion or frustration which lie beneath.

Effective reparation is not just a throw-away plaster, but indelible medicine for the heart and soul.

So what is this magic elixir and how do I get some?

Sarah’s Sock Monsters

Sarah recounts a recent example of ‘rupture and repair’ in her household.

We have a chronic odd sock problem, honestly we have a whole basket full of them. In my effort to get the children to help with the housework last night I tried, unsuccessfully, to make pairing the socks playful. (Thinking PACE here! See last week’s blog for more on this…)

The boys (10, 8 and 3) were all keen and I suggested we see who could make more pairs.

First mistake. Given the level of competitiveness between the oldest two, I should have done it as a joint task.

They were still on board despite this, and my eight year-old came upstairs with the little one whilst the eldest went to get some food.

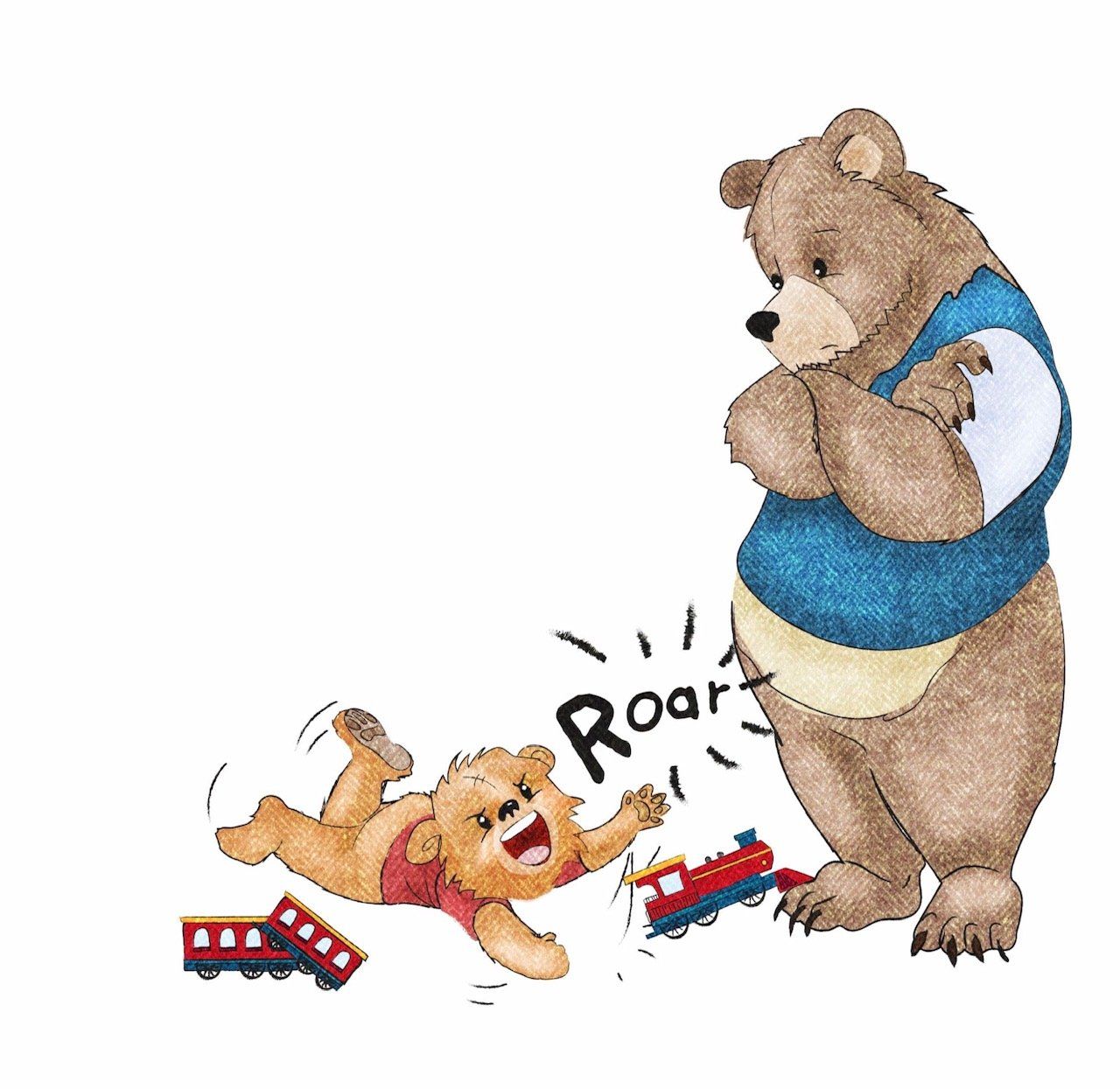

Disaster struck when he returned to see that the others had started without him.

I could see the inevitable coming, so I intervened asking him not to over-react. This was my second mistake.

It led to a pretty monstrous meltdown: the basket was pulled from his brothers, socks - all of them - were strewn over the floor and, after screaming loudly about how unfair it was, how mean I was and how I prefer his brothers to him, he fled to his room in a rage where he began crying.

I realised that I had made a boo boo on a number of levels and needed to connect with him and apologise for my errors - despite feeling highly frustrated that a bit of fun had turned nasty and that his over-reaction seemed so out of proportion.

I reminded myself that it wasn't about the socks, but about his feelings of others being prioritised which made him feel he was not valued as much.

I went into this room and said that I was sorry we had started without him (he started to soften and stopped telling me to go away) and that I had not intended to make him feel left out.

I said that it must have felt unfair and that it seemed like I was letting the others succeed when he was at a disadvantage (he softened further!), I told him that I had not intended to make him feel bad and was sorry that I had and that I understood his reaction - although it would be helpful if we could have found another way to tell me how much it upset him.

I said that I had intended to ask the others to stop when he came up from food so it would be more fair, but that I was sorry I wasn't clear about that and he felt so left out.

I tried to match this all with acceptance and empathy as well as being present and having some spe-cial time with him afterwards.

This response (which I don't always manage) worked wonders and he joined in again, joking with his brothers. He even managed an almost sincere apology for pulling his brother’s hair (oh yes, that happened too!) and we had a lovely remainder of the evening.

He crept into my bed later that night, which I think was his way to reconnect with me after feeling I wasn’t really against him.

Notes to self:

• Some children are more sensitive.

• All children, to some degree, struggle with sibling rivalry and tonight it revealed his feelings - which we all have at one time or another - that others are better than him.

• I must try to look at the hidden rather than expressed feelings (it really wasn't about the socks) and make sure I acknowledge how big they are for the little in question and help them with them.

He gave me a gorgeous wave when he went off to school this morning - much nicer than the times he holds a grudge and snarls at me when I haven't effectively repaired.

I do still have odd socks all over my floor though!

Relax, you’ve got this…

Even if your plasters have Paw Patrol on them, your kids will appreciate the healing power of effective repairing actions much more.

Sarah employed some key strategies to make this happen (more details are in the ‘Parenting Hand-book’, which accompanies the lift-the-flap books):

Reflecting

- on what happened rather than moving on, chastising or ignoring the behaviours and the feelings

Empathising

- with the feelings the event threw up (even if they seemed out of proportion)

Labelling

- the feelings, and thus allowing her son to understand and manage them. They’re less scary when they are explained as normal and the child is helped to understand them.

Apologising

- for her part in adding fuel to the fire.

Accepting

- the big feelings and blow outs as natural. We can help our kids learn to control them and deal with them over time in less demonstrative ways.

X

- kisses, hugs and cuddles

Over time, the act of repairing ruptures in your relationship with your kids nurtures their deep-rooted emotional durability…when they do go wrong they know they are loved, unconditionally.

In essence, this approach can make them happier humans.

Adulting = check

Acknowledging mistakes and using them to help grow your children’s mental well-being - crikey, that sounds very mature. Is this, in fact, adulthood?

We perhaps don’t have a clue, sometimes. Or even very often. But we’re doing our best to figure it all out. And that is enough.

(But seriously, WHAT HAPPENS TO THE SOCKS?)

.

.

.

Next week, we meet another key team-member, Claire - our marketing and PR whizz - and explore the next element of the PACE model: acceptance.

Happy hero-ing everyone. xBecks

Editor. Blogger.

@rebeccaritsonwrites

www.rebeccaritson.com

Follow us on the links below! 1 month 9 days days to the Crowdfunder launch :)

Little children can be so confusing (and confused!). Sometimes it’s hard to know what they need from you - a three-year-old demands that she wants her cheese in a big piece one day and then cries because it’s not cut up the next. She wants you to hold her hand to go to the toilet in the morning, but later gets cross when you try to do the same. We’ve all been there, faced with the - sometimes baffling - behaviours of the small humans that surround us, wondering how to respond to their inconsistent requests. Perhaps it’s reassuring to realise that these seemingly random behaviours are actually quite natural - stages through which each child progresses. In a bid to help you support your growing pre-schoolers more effectively, this blog talks about some of the things (there are many!) happening inside their heads and how you can support them with what’s going on. What’s Happening Inside a Three-Year-Old’s Brain?

What was your favourite story when you were growing up? Was it a traditional fairy tale like Cinderella? Was it a popular picture book like The Very Hungry Caterpillar or The Gruffalo? Or was it a great adventure story like CS Lewis’ Narnia series or JK Rowling’s Harry Potter? Mine was Dogger by Shirley Hughes. Funny that the first book I wrote was about separation anxiety! For many of us, sharing and reading books was an important part of childhood, even more so before the advent of distracting screens and 24/7 streaming. I have fond memories of curling up in bed, half asleep, as my mum or dad read to me complete with silly voices and giggles aplenty. It's not just books though - you can make your own stories up too. I tell my little one a story about “Grizzly Bear with the Curly Hair” every night. It’s evolved to be a lovely family tradition, with my older children sometimes coming to join in. This is a wonderful way to stimulate both mine and my children’s imagination and what I most love about it is how the narrative is co-constructed – I am no longer allowed to be the sole story-teller, my son has to be part of it too! A 2018 research study found that nowadays only 30% of parents read to their children daily and I can’t help feeling that’s a bit sad. Especially given the many benefits of sharing story time go far beyond pure entertainment.

I thought I’d do a post on guilt and shame, feelings which are often used interchangeably but, from my understanding are pretty different. A quick whizz through some child development When we are little, particularly when we start testing the boundaries during toddlerhood, parents need to intervene to keep children safe. For those of you with little ones the word “NO” probably comes out more than you would like it to! This is a normal part of development – children exploring without an understanding of risks, and needing adult involvement to know when to stop. When a child is asked to stop doing something, which was most probably led by curiosity (can I touch that hot thing in the fire place?!), they are likely to experience shame. It’s not a nice feeling but is quickly regulated when a parent explains their motive and repairs the rupture in the relationship. “I’m sorry that I raised my voice, I know you were just exploring but it’s dangerous to touch fires” and so on. This gives the message that the parent is still there for the child and that they are accepted for who they are. The parent is showing them that their behaviour not OK, but that they are. This sort of parenting, when reasonably consistent, leads to a child feeling guilt rather than shame. “Oops, I shouldn’t have done that, how can I make amends?” (obviously not so clearly thought out for little ones but you get the gist). .

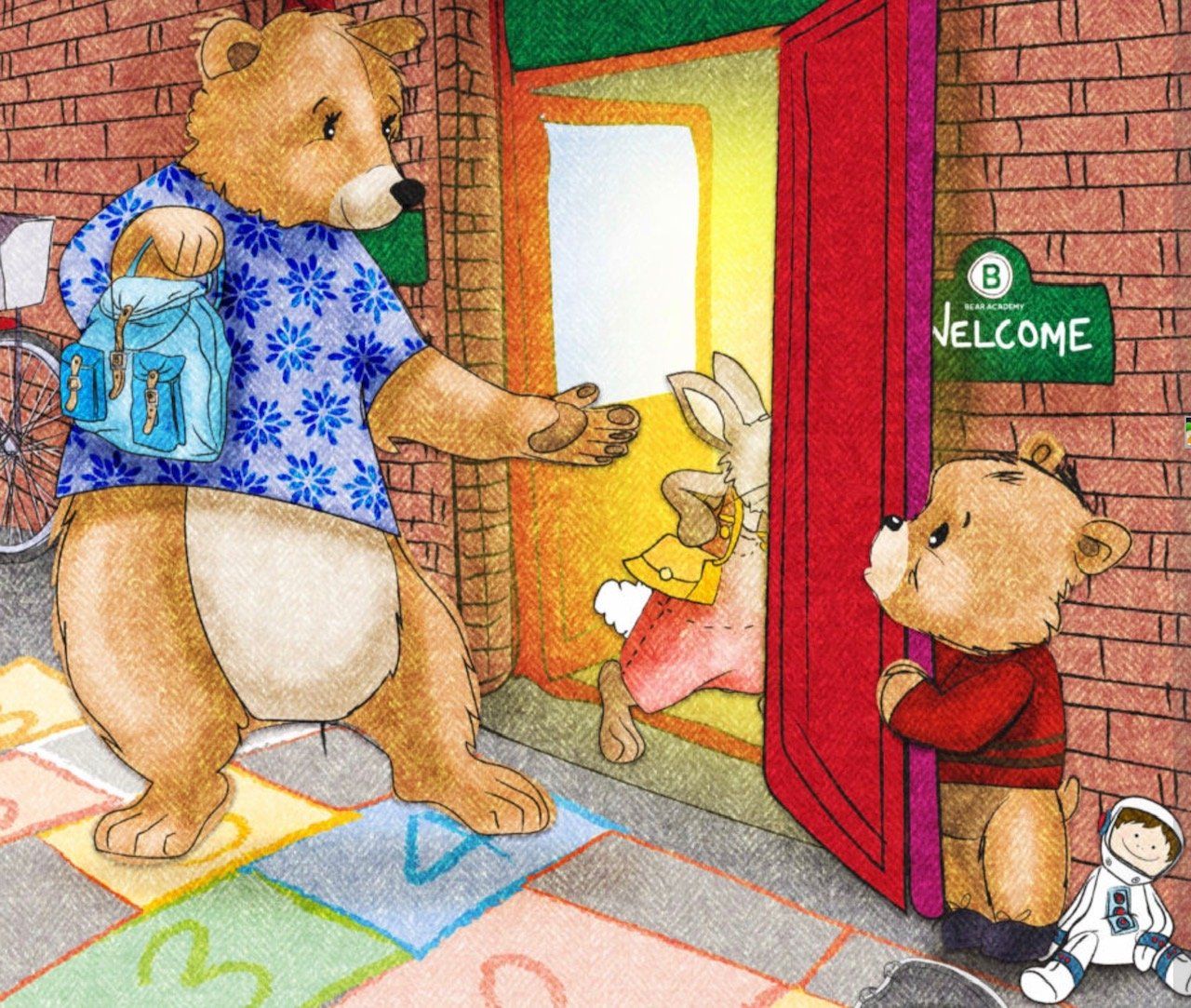

As a newborn, we look to our parents for everything. To feed us, to comfort us and to protect us. If they give us this safety and security, a healthy emotional bond develops. Research shows that this attachment relationship is a crucial building block of a child’s development, helping them to grow socially, emotionally, behaviourally and intellectually. But what happens when children begin to spend time with other caregivers, outside of the home and away from their parents? Do they develop similar relationships with the nursery staff, childminders or pre-school teachers that look after them? And what does this mean for you if you’re working in Early Years?

If you work in an early years setting, you’ll be quite familiar with the scene. You’re welcoming the children and getting them settled at the start of the day, checking in with them and showing them what activities you have planned. Suddenly, you hear shouting and crying as a stressed-looking mum tries to detach her small child from her leg. You feel for her, you really do; this child regularly clings to her on arrival - the anxiety is palpable. It’s distressing for everyone involved. For Mum, for the child, for the other children who are already in the room, and not least for you. You know from experience that they will settle down and be OK, but that doesn’t make it any easier in the moment. And you know, too, that poor Mum has headed off to work feeling guilty and upset, so it’s unsurprising when she phones 15 minutes later seeking reassurance from you. These experience are likely to be more pronounced at the moment, with children having fewer, if any, opportunities to practice separating from their parents, with collective anxiety at a huge level and with normal settling in sessions, with parents in the room, being unavailable. What is separation anxiety?

Where do I start? Attachment is a HUGE topic, with decades of research highlighting how important it is to a child’s development. But do you know what an attachment relationship actually is? And why it’s so important? Do you know what helps children develop more secure attachment relationships? With different approaches and a number of terms banded around it can feel so confusing. This blog addresses these questions and focuses upon ways that parents and educational settings can put attachment theory into practice. It is based upon my experience as a Clinical Psychologist. For over 15 years I have been drawing upon attachment theory to inform my work with parents and children. I’ve tried to ensure that my suggestions are user-friendly. As a mum of three I have learnt that theory does not always feel that easy to translate into practice. We can feel pressured to get it right all of the time (apologies to the clients I worked with before having my own children!). The beauty of attachment theory is that we don’t have to be perfect. Just good enough. As with anything scientific there can be a lot of jargon – I have put the key words in italics and tried to write with minimal psychobabble. I do hope you enjoy it! What is attachment (in a nutshell)?

In case you hadn’t noticed, Christmas is coming, and fast! It’s different this year, without nativity plays, big get togethers and light turn-ons. But it’s still happening, as both we, and our children well know! My three-year-old is already telling me that it is “Christmas tomorrow” on a daily basis (to be fair he also thinks it’s still Halloween so he’s not particularly accurate in his understanding of seasonal activities!). He is, however, starting to get excited. He’s remembering the elves escapades from last year, asking when they are coming back (I still haven’t found them in my cluttered house!). Why I added the nightly task of creating funny Elf scenes throughout December to the already huge list of Christmas jobs is beyond me, but at least he likes it! I was also quite proud of last year’s zip wire adventure.

I know the gold standard for writing blogs is to deliver them on a fortnightly basis. I’ve been a bit remiss as this is my first one in months! What a better topic to start with then than why it is OK not to get things right all the time. Perfection is unobtainable, but it does seem to be something that we are pushed to do. The number of posts out there on mum guilt is astonishing. Over the last year we have been expected to juggle life in a way that does not seem possible. Many of us have been coping with (or trying to) being teachers, parents and professionals, three full time jobs all at the same time! This has left me wondering whether it’s actually possible to do anything well enough! And then along comes Christmas (gulp!). I’m hoping that reading this will leave you feeling happier with how you are doing as a parent, that you will realise that buying into the pressure to get it “right” is not helpful, and that you will learn that the attachment research highlights how we don’t need to be perfect to raise happy and healthy children. Children don’t need us all of the time. They need is a parent who knows they are good enough for them, accepts their foibles, makes and owns mistakes, and can manage their own emotional world. Forget Perfection - Strive for Good Enough Parents can feel a great deal of guilt around their work/life balance. Guilt can actually be a helpful emotion, allowing you to reflect on what is, and isn’t working. However, when you have little control over the things you want to change, it can feel overwhelming. The first thing you need to remember is that you are doing your best, and that is good enough. Interestingly, an article in the Economist reported that we spend twice as much time with our children as parents did 50 years ago (The Economist, November 27th 2017), suggesting that we are already much more active in our parenting than we used to be. “Good enough” is key to parenting. Research into attachment, which is important to children’s development, highlights how we should strive to be good enough, not perfect. A recent study on infant attachment found that parents need to be “in tune” with their babies about 50% of the time in order to develop secure attachment relationships (Woodhouse et al., 2019). So, if you’re getting it right about half the time, you’re onto something! Quality of Time is Far More Important than Quantity

Well what a year it has been. Not one that any of us could have imagined or would have hoped for. All over the world we are having to adapt to the threat of Covid-19 and uncertainty about the future. Children have had prolonged periods away from education and, although some of them are back, this can be on and off as and when Covid-19 dictates. Helping children cope with these changes is key for the education sector if we are to support them to re-engage in learning. As a Clinical Psychologist I have been working with schools as well as children and families over this difficult period. I wrote this blog to summarise some of the ways educational professionals can support children through the increased anxiety they are likely to be feeling. Anxiety and Covid-19 A global pandemic is not good for anyone’s emotional wellbeing and is having an impact upon us all. Whilst we are all in very different situations, it is far from what any of us are used to and children will be noticing these changes. They are likely to be seeing more worried adults, hearing more stressful news and having little, if any, time with friends. Children have had to contend with new rules, a change in routine, a lack of control and a loss of relationships. Like us, they feel safe when things are predictable – something which has been absent for many months now.

We can't always live in harmony with our little ones, sometimes our agendas feel miles apart. For me most of the ruptures come early in the morning, when my little one is pulling my nightie up saying "milk" and I am saying "sleep". My parenting powers aren't at their best at 5:30 and I often become cross (yup, I tell him to stop being annoying and to let me sleep). So, when this happens it really is my responsibility to repair the rupture. The behaviour really is annoying, but it's not helpful for him to hear that he's annoying when all he wants is a drink! In a previous post I talked about the importance of repairing your relationship with your little one after a rupture - here are some of the ways to do it. Establish safety in your relationship . When children feel safe and supported they will still do things that challenge you! However, the more secure they feel with you the less likely they are to feel that you are angry at them, or think they are bad, and instead may be able to learn that you will love them no matter what. This bodes well for those times that you are not on the same page and are needing to put in the boundaries. Remain accountable in your words, feelings and choices. When I am finding my partner frustrating it is not always his fault (but don't tell him that!). It's often when I am tired and busy and he is not getting what I need. We both need to take responsibility for finding a way forward, communicating well, acknowledging our feelings and being clear about what we need. Little ones don't quite have the skills for this yet and it is our job to model them how we manage ruptures. So do try to think about whether you would have responded differently were you not so knackered, consider what their behaviour was communicating (there's always a reason!) and try to be clear in how you discuss what happened. We do need to help little ones learn but it's also very helpful if they can see what part we played. For example, after I have calmed down from being woken at 5:30 I apologise to my little one for being cross. I tell him that sleep is important and that it makes me grumpy if he wakes me up early. I also try to think more broadly about what would have helped - for example, making sure he was well fed and watered before bed and getting myself into a better routine. What is important is that he hears I am not blaming him for being hungry and waking up at the time his body clock is set to wake! Know what to say (or not to say) and when to talk (or not talk) If you are anything like me you might want to have the last word, or show that you are right. Particularly in the moment! Whilst it would be more helpful if I did not feel the need to do this, especially with my pre-schooler, I do know it's a trait of mine. It's important to learn to read what is going on - is it really the time to engage in a battle with them when everyone is exhausted? Think about what purpose it will serve (probably make you feel more distant). It's OK to revisit at a later time. When you are talking to your child about tricky times, try to be curious, talk about unhelpful behaviours, explain how you understood what happened (what feelings were driving their behaviour), talk about your part in the rupture, apologise and say what you could have done differently. What a great model for children to see parents showing they understand, are interested in what's going on and make mistakes themselves. So much more healthy than punishing - remember discipline is about teaching, not making children feel bad or naughty.